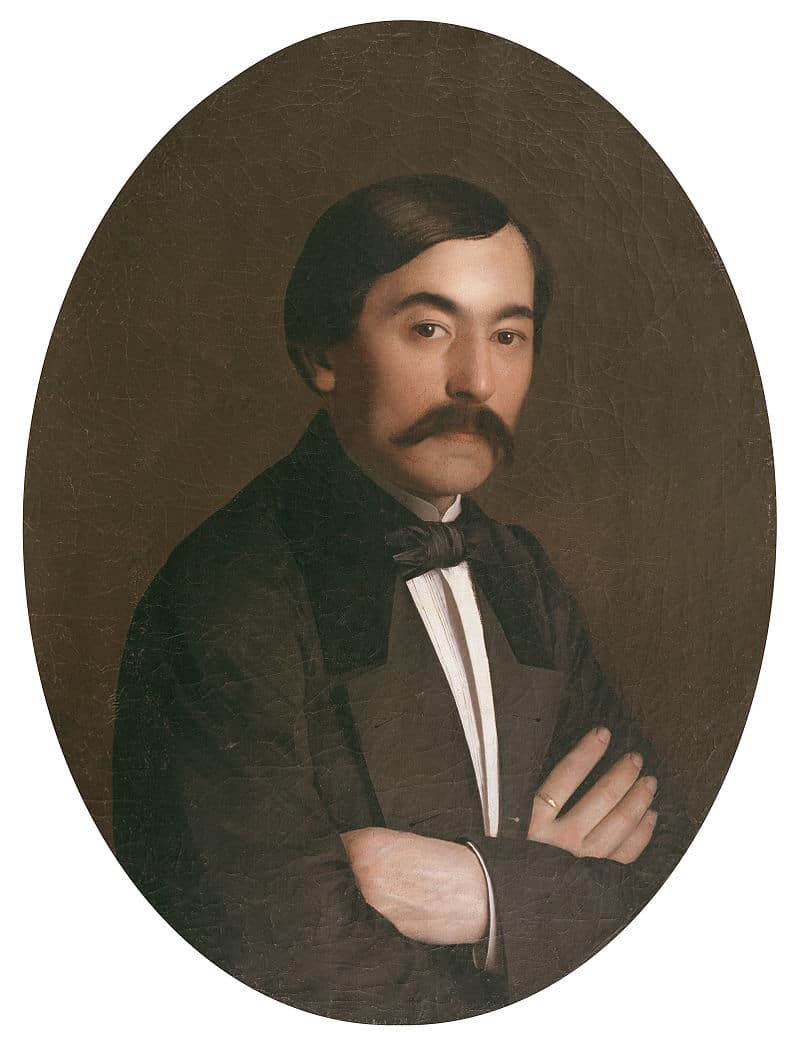

Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard (P.G.T. Beauregard) was an officer during the Civil War that served with distinction for the Confederate States of America. He was influential in the defense of Petersburg and South Carolina and was present during the firing on Fort Sumter.

Although he did not have a great relationship with President Jefferson Davis throughout the war, he and his fellow officer Joseph E. Johnston convinced Davis to surrender to the Confederacy. After the war, he became a successful railroad executive and promoter of the Louisiana lottery.

Early Years

Beauregard was born at the "Contreras" sugar cane plantation in St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, about 20 miles outside New Orleans, to a French Creole family.

Beauregard was the third child of Hélène Judith de Reggio, of mixed French and Italian ancestry and descendant of Francesco M. de Reggio, a member of an Italian noble family whose family had migrated first to France and then to Louisiana, and her husband, Jacques Toutant-Beauregard, of French and Welsh ancestry.

He had three brothers and three sisters. His family was Roman Catholic. Beauregard attended New Orleans private schools and then went to a "French school" in New York City.

During his four years in New York, beginning at age 12, he learned to speak English, as French had been his first and only language in Louisiana.

He then attended the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. One of his instructors was Robert Anderson, who later became the commander of Fort Sumter and surrendered to Beauregard at the start of the Civil War.

Upon enrolling at West Point, Beauregard dropped the hyphen from his surname and treated Toutant as a middle name to fit in with his classmates. From that point on, he rarely used his first name, preferring "G. T. Beauregard." He graduated second in his class in 1838 and excelled both as an artilleryman and military engineer.

His Army friends gave him many nicknames: "Little Creole," "Bory," "Little Frenchman," "Felix," and "Little Napoleon."

Military Career

Beauregard had a prestigious military career before the outbreak of the Civil War. He served as an engineer during the Mexican-American War under General Winfield Scott.

He was appointed brevet captain for the battles of Contreras and Churubusco and major for Chapultepec, where he was wounded in the shoulder and thigh. He was noted for his eloquent performance in a meeting with Scott in which he convinced the assembled general officers to change their plan for attacking the fortress of Chapultepec.

He was one of the first officers to enter Mexico City. Beauregard considered his contributions in dangerous reconnaissance missions and devising strategy for his superiors to be more significant than those of his engineer colleague, Captain Robert E. Lee, so he was disappointed when Lee and other officers received more brevets than he did.

Beauregard returned from Mexico in 1848. For the next 12 years, he was in charge of what the Engineer Department called "the Mississippi and Lake defenses in Louisiana." Much of his engineering work was done elsewhere, repairing old forts and building new ones on the Florida coast and in Mobile, Alabama.

He also improved the defenses of Forts St. Philip and Jackson on the Mississippi River below New Orleans. He worked on a board of Army and Navy engineers to improve the navigation of the shipping channels at the mouth of the Mississippi. He created and patented an invention he called a "self-acting bar excavator" to be used by ships in crossing bars of sand and clay.

While serving in the Army, he actively campaigned for the election of Franklin Pierce, the Democratic presidential candidate in 1852 and a former general in the Mexican War who had been impressed by Beauregard's performance in Mexico City.

Pierce appointed Beauregard as superintending engineer of the U.S. Custom House in New Orleans, a huge granite building that had been built in 1848. As it was sinking unevenly in the moist soil of Louisiana, Beauregard had to develop a renovation program. He served in this position from 1853 to 1860 and stabilized the structure successfully.

During his service in New Orleans, Beauregard became frustrated as a peacetime officer. During this time, he flirted with the idea of joining William Walker, who ad seized control of Nicaragua, as second in command of the expedition.

On the advice of Winfield Scott, he opted to stay out of the conflict and remain in the country. He then had a short career in politics when he was narrowly defeated in his bid for mayor of New Orleans.

He was given a position as superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy, which was revoked five days later when Louisiana seceded from the Union. Beauregard complained that he was unfairly dismissed as a Southern officer, but his complaints were never addressed, and he returned home to Louisiana.

Civil War

Upon returning home, Beauregard immediately began giving military advice to the local authorities in Louisiana and put his engineering skills to work. He gave expert advice on how to strengthen several forts throughout the South, including Fort Sumter.

Concerned about the political situation regarding the Federal presence at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, Jefferson Davis selected Beauregard to take command of Charleston's defenses.

Beauregard seemed the perfect combination of military engineer and charismatic Southern leader needed at that time and place.

Beauregard served courageously throughout the Civil War. Here is a list of events he participated in:

- Fort Sumter: He was the senior commander onsite and tried to negotiate with his former instructor, Major Anderson, before ordering Sumter to be fired on.

- First Battle of Bull Run: Beauregard served with distinction during the First Battle of Bull Run. Beauregard devised many of the strategies that would be employed, which led to his first of many conflicts with Jefferson Davis, why believed Beauregard to be impractical. However, Beauregard and Johnston defeated the Union Army.

- Shiloh: The first day of the Battle of Shiloh was a great success for Beauregard and his men. However, after the first night, Beauregard rested his men, believing that he could finish Ulysses Grant off in the morning. He was surprised the next day when Grant's army was reinforced, and they overwhelmed the Confederates, pushing them back to Corinth.

- Corinth: While in Corinth, Beauregard employed a strategic retreat in which he tricked the Union into thinking he was planning an attack. Men would cheer when empty trains drove into the station, leading the Union to believe they were receiving reinforcements. He successfully withdrew from Corinth but received much criticism for abandoning an important railroad connection without a fight.

- Return to Charleston: Beauregard had taken leave without proper notice and was subsequently replaced with General Braxton Bragg and reassigned to the coastal defense of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. Although unhappy, he performed well and prevented the capture of Charleston. He employed advanced naval tactics with experimental submarines, mines, and torpedo rams. During this time, his wife passed away in Union-occupied New Orleans.

- Petersburg: After Cold Harbor, Lee and the Confederate high command were unable to anticipate Grant's next move, but Beauregard's strategic sense allowed him to make a prophetic prediction: Grant would cross the James River and attempt to seize Petersburg, which was lightly defended, but contained critical rail junctions supporting Richmond and Lee. Despite persistent pleas to reinforce this sector, Beauregard could not convince his colleagues of the danger. On June 15, his weak 5,400-man force, including boys, old men, and patients from military hospitals, resisted an assault by 16,000 Federals, known as the Second Battle of Petersburg. He gambled by withdrawing his Bermuda Hundred defenses to reinforce the city, assuming correctly that Butler would not capitalize on the opening. His gamble succeeded, and he held Petersburg long enough for Lee's army to arrive. It was arguably his finest combat performance of the war.

- Sherman's March: William T. Sherman began his march to the sea and then continued northward. Beauregard could do little to stop him as the Confederate army was badly damaged and did not have many men left with fighting ability. Beauregard was replaced due to his feeble health with Joseph Johnston and would remain his subordinate until the end of the war. He and Johnston would surrender their forces in Durham, North Carolina.

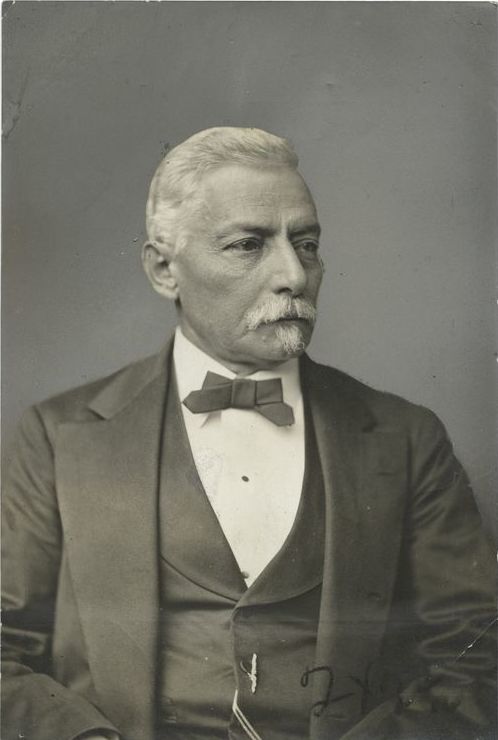

Post War Life

Beauregard's first employment following the war was in October 1865 as chief engineer and general superintendent of the New Orleans, Jackson, and Great Northern Railroad. In 1866, he was promoted to president, a position he retained until 1870, when he was ousted in a hostile takeover.

This job overlapped with that of the president of the New Orleans and Carrollton Street Railway (1866–1876), where he invented a system of cable-powered street railway cars. Once again, Beauregard made a financial success of the company but was fired by stockholders who wished to take direct management of the company.

In 1869, he demonstrated a cable car and was issued U.S. Patent 97,343.

After the loss of these two railway executive positions, Beauregard spent time briefly at a variety of companies and civil engineering pursuits, but his personal wealth became assured when he was recruited as a supervisor of the Louisiana Lottery in 1877.

He and former Confederate general Jubal Early presided over lottery drawings and made numerous public appearances, lending the effort some respectability. For 15 years, the two generals served in these positions, but the public became opposed to government-sponsored gambling, and the lottery was closed down by the legislature.

Beauregard's military writings include

- Principles and Maxims of the Art of War (1863)

- Report on the Defense of Charleston

- A Commentary on the Campaign and Battle of Manassas (1891).

He was the uncredited co-author of his friend Alfred Roman's The Military Operations of General Beauregard in the War Between the States (1884). He contributed the article "The Battle of Bull Run" to Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine in November 1884.

During these years, Beauregard and Davis published a series of bitter accusations and counter-accusations, retrospectively blaming each other for the Confederate defeat.

Beauregard served as adjutant general for the Louisiana state militia, 1879–88. In 1888, he was elected as commissioner of public works in New Orleans. When John Bell Hood and his wife died in 1879, leaving ten destitute orphans, Beauregard used his influence to get Hood's memoirs published, with all proceeds going to the children.

He was appointed by the governor of Virginia to be the grand marshal of the festivities associated with the laying of the cornerstone of Robert E. Lee's statue in Richmond. But when Jefferson Davis died in 1889, Beauregard refused the honor of heading the funeral procession, saying, "We have always been enemies. I cannot pretend I am sorry he is gone. I am no hypocrite."

Beauregard died in his sleep in New Orleans. The cause of death was recorded as "heart disease, aortic insufficiency, and probably myocarditis." Edmund Kirby Smith, the last surviving full general of the Confederacy, served as the "chief mourner" as Beauregard was interred in the vault of the Army of Tennessee in historic Metairie Cemetery.

P.G.T. Beauregard: Online Resources

- Wikipedia - Beauregard

- Civil War Trust - P.G.T. Beauregard Bio

- P. G. T. Beauregard: Napoleon in Gray (Southern Biography Series)

- Beauregard-Keyes House

- Find a Grave - P.G.T. Beauregard

- P.G.T. Beauregard Family Tree

- The History Junkie's Guide to the Civil War

- The History Junkie's Guide to Civil War Genealogy