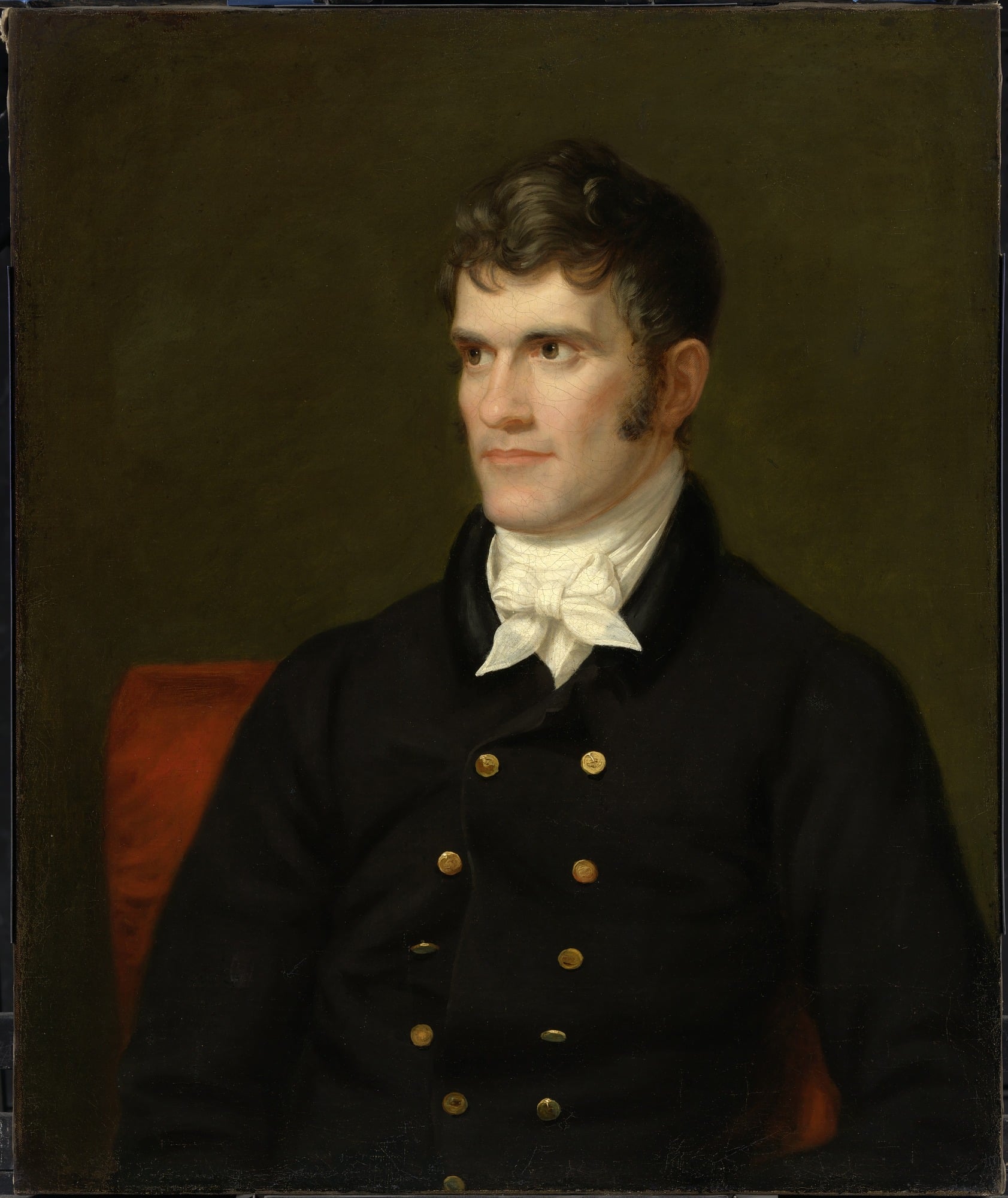

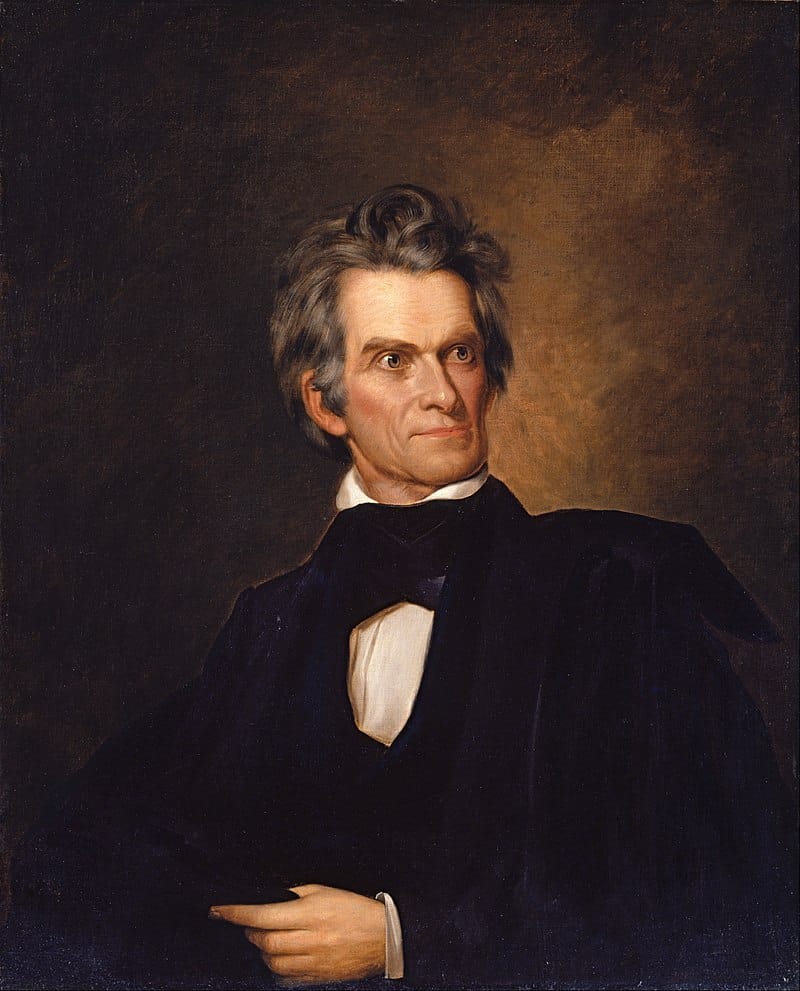

John Calhoun was an American statesman and political theorist from South Carolina. He held every major post except the president, serving in the House, Senate, and vice presidency, as well as secretary of war and state.

A powerful intellect, John Calhoun eloquently spoke out on every issue of his day from 1812 to 1850 but is best known for his intense and original defense of slavery as a positive good and for pointing the South toward secession from the Union.

He usually affiliated with the Democrats but flirted with the Whig Party and considered running for the presidency in 1824 and 1844. Starting as a leading nationalist and modernizer, after 1828, Calhoun reversed directions and became the foremost spokesman for states' rights and slavery.

Devoted to the principle of liberty and fear of corruption, Calhoun expanded the notion of republicanism to include the need to protect minority rights against majority rule; his approach was the "concurrent majority."

Increasing distrustful of democracy, he minimized the role of the Second Party System in South Carolina. The leaders of the secession movement in the decade after his death looked to Calhoun as a hero.

Jump to:

Personal life

Calhoun was born in Abbeville, South Carolina, in 1782 into a Scotch-Irish family that had emigrated from Ireland to Pennsylvania in 1733, then moved down the Appalachian Mountain valley into the South Carolina backcountry in the 1760s.

His father became rich, owning lands and 20 to 40 slaves in a region where slaves were not yet common. Life was still raw and rough on the frontier, and violence was very much part of people's memories: his father's mother had been killed by Cherokee Indians in 1760, and his mother's brother, John Caldwell, after whom he was named, had been murdered by Loyalists during the American Revolution.

His father, who had survived the Indian massacre of 1760, had stubborn independence and, as Calhoun recalled, "a certain degree of contempt for the forms of civilized life." He had a passion for liberty and a deep dislike of far-removed government; he opposed ratification of the federal Constitution on the grounds that "we ought never to give others the power to tax us." His father died in 1795 when John was only 13.

In a very unusual move for the era, the young man went to New England to attend Yale College, graduating in 1804, then studied law at one of the nation's first law schools, run by Tapping Reeve at Litchfield, Connecticut.

After further training in Charleston, South Carolina, he was admitted to the bar in 1807 and began practice near his family home. In 1811, he married Floride Bonneau Colhoun, a wealthy second cousin who provided entree to high society in Charleston.

They had nine children and lived at "Fort Hill," a cotton plantation he built and operated by a white overseer and dozens of slaves. He had a substantial but routine law practice and was soon bored. He was elected as a Jeffersonian Republican to the state legislature in 1808 and to Congress in 1810.

Like so many ambitious young politicians who came of age after the Constitution took effect in 1789, Calhoun was profoundly shaped by the Founding Fathers' faith in the potential of republican government.

Calhoun, probably a Deist, never joined a church; he closely followed the austere moralism of his Scotch-Irish Presbyterian ancestors and was never tempted to gamble, womanize, or drink to excess. He was a faithful, if often self-absorbed, partner in a sometimes stormy marriage to Floride. Despite his austere image, he was a loving and surprisingly permissive father.

Calhoun was also an exemplary slaveholder who "probably lived up to the just master's ideal as well as anyone."

War Hawk

Although he had little charisma or charm, Calhoun was a brilliant orator and strong organizer and immediately became a leader of the "war hawks," along with Speaker Henry Clay and South Carolina congressmen William Lowndes and Langdon Cheves.

They disregarded European complexities in the wars between Napoleon and Britain, brushed aside the vehement objections of New Englanders, and demanded war against Britain to preserve American honor and republican values.

Clay made Calhoun the acting chairman of the powerful committee on foreign affairs. On June 3, 1812, Calhoun's committee called for a declaration of war in ringing phrases. The episode spread Calhoun's fame nationwide.

War - the War of 1812 - was declared, but it went very badly for the poorly organized Americans, whose ports were immediately blockaded by the British Royal Navy. An attempted invasion of Canada was a total fiasco.

Calhoun labored to raise troops, provide funds, speed logistics, improve the currency, and regulate commerce to aid the war effort. Disasters on the battlefield made him double his legislative efforts to overcome the obstructionism of John Randolph Daniel Webster and other opponents of the war.

Once Napoleon had been sent off to exile in Elba, the two nations had no further cause to fight, and peace was achieved at Ghent on Christmas, 1814.

Before that news reached New Orleans, a massive British invasion force was utterly defeated at the Battle of New Orleans, which made a national hero out of General Andrew Jackson.

Early Political Career

Calhoun continued his role as a leading nationalist during the "Era of Good Feeling" during the Monroe administration, 1816-25. He proposed an elaborate program of national reforms to the infrastructure that would speed economic modernization.

His first priority was an effective navy, including steam frigates, and in the second place, a standing army of adequate size; and as further preparation for emergency "great permanent roads," "a certain encouragement" to manufactures, and a system of internal taxation which would not be subject like customs duties to collapse by a war-time shrinkage of maritime trade.

He spoke for a national bank, for internal improvements (such as harbors, canals, and river navigation), and a protective tariff that would help the industrial Northeast and, especially, pay for the expensive new infrastructure. The word "nation" was often on his lips, and his conscious aim was to enhance national unity, which he identified with national power.

One observer commented that Calhoun was "the most elegant speaker that sits in the House... His gestures are easy and graceful, his manner forcible, and language elegant; but above all, he confines himself closely to the subject, which he always understands, and enlightens everyone within hearing; having said all that a statesman should say, he is done."

His talent for public speaking required systematic self-discipline and practice. A later critic noted the sharp contrast between his hesitant conversations and his fluent speaking styles, adding that Calhoun "had so carefully cultivated his naturally poor voice as to make his utterance clear, full, and distinct in speaking and while not at all musical it yet fell pleasantly on the ear."

After the war ended in 1815, the "Old Republicans" in Congress, with their Jeffersonian ideology for the economy in the federal government, sought at every turn to reduce the operations and finances of the war department.

In 1817, the deplorable state of the war department led four men to turn down requests to fill the secretary of war position before Calhoun finally accepted the task. Political rivalry, namely, Calhoun's political ambitions, as well as those of William H. Crawford, the secretary of the treasury, over the pursuit of the 1824 presidency, also complicated Calhoun's tenure as war secretary.

Calhoun proposed an expansible army similar to that of France under Napoleon, whereby a basic cadre of 6,000 officers and men could be expanded into 11,000 without adding additional officers or companies. Congress wanted an army of adequate size in case American interests in Florida or the West led to war with Britain or Spain.

However, the nation was satisfied by the diplomacy that produced the Convention of 1818 with Britain and the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819 with Spain. The need for a large army disappeared, and Calhoun could not prevent cutbacks in 1821.

As secretary, Calhoun's had responsibility for the management of Indian affairs. A reform-minded modernizer, he attempted to institute centralization and efficiency in the Indian department, but Congress either failed to respond to his reforms or responded with hostility.

Calhoun's frustration with congressional inaction, political rivalries, and ideological differences that dominated the late early republic spurred him to create the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1824 unilaterally. He supervised the negotiation and ratification of 38 treaties with Indian tribes.

Calhoun sought the presidency in 1824 but settled for second place under John Quincy Adams and played a minor role as vice president. In 1828, he supported Andrew Jackson and was again elected vice president. They broke in 1831.

Nullification

John Calhoun aggressively championed nullification, which allows individual states to cancel a federal law it considers unconstitutional. It derives from and goes beyond the "Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions" of 1798, written by Jefferson and Madison, that had been a bedrock principle throughout the South; James Madison said Calhoun went too far.

He was the secret author of the South Carolina Exposition and Protest, a document that advocated the nullification of the Tariff of 1828. The tariff was so high that it was "unconstitutional, unequal and oppressive; and calculated to corrupt public virtue and destroy the liberty of the country."

The Exposition was submitted to the South Carolina legislature as a resolution, but it was not passed.

Nullification Crisis: 1833

In 1832, the South Carolina legislature passed a resolution that declared the federal tariff of 1828 void.

President Andrew Jackson was incensed, and Congress passed the Force Bill, threatening military intervention. The issue, as Jackson saw it, was not the tariff but obedience to federal law. He threatened to call out the troops and to hang Calhoun "higher than Haman" if he got hold of him.

John Calhoun resigned from the vice presidency, accepted election as senator from South Carolina, and returned to Washington. No one was hanged as Henry Clay brokered a compromise between Jackson and Calhoun. No southern state stood by South Carolina.

Calhoun's followers believed republican values were safe only at the state level, but he ignored the tyranny of the majority at the state level. He did not champion the rights of the individual. Daniel Webster argued, in contrast, that republican values were secure only at the national level.

Most historians argue that nullification was a reactionary effort to turn back the abolitionist assault on slavery.

Democratic politics

To restore his national stature, Calhoun cooperated with Jackson's success, Martin Van Buren, who became president in 1837. Democrats were very hostile to national banks, and the country's bankers had joined the opposition Whig Party.

The Democratic replacement was the "Independent Treasury" system, which Calhoun supported and which went into effect. Calhoun, like Jackson and Van Buren, raged against finance capitalism, which he saw as the common enemy of the Northern laborer, the Southern planter, and the small farmer everywhere.

His goal, therefore, was to unite these groups in the Democratic Party and to dedicate that party to states' rights and agricultural interests as barriers against encroachment by government and big business.

When Whig President William Henry Harrison died after a month in office in 1841, Vice President John Tyler took office. Tyler was a Democrat who broke bitterly with the Whigs and named Calhoun Secretary of State in 1844.

Public opinion was inflamed about the Oregon country, claimed by both Britain and the U.S. Calhoun compromised by splitting the area down the middle at the 49th parallel, ending the wear threat. Tyler and Calhoun were eager to annex the independent Republic of Texas, which wanted to join the Union.

Texas was a slave country, and anti-slavery elements in the North denounced annexation as a plot to enlarge the Slave Power (that is, the excess political power controlled by slave owners).

When the Senate could not muster a ⅔ vote to pass a treaty of annexation with Texas, Calhoun devised a joint resolution of the Houses of Congress, requiring only a simple majority; Texas joined the Union. Mexico had warned all along that it would go to war if Texas joined the Union; war broke out in 1846.

Rejects Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850, devised by Clay and Democratic leader Stephen A. Douglas, was designed to solve the controversy over the status of slavery in the vast new territories acquired from Mexico. John Calhoun, back in the Senate but too feeble to speak, wrote a blistering attack on the compromise.

A friend read his speech, calling upon the Constitution, which upheld the South's right to hold slaves; warning that the day "the balance between the two sections" was destroyed would be a day not far removed from disunion, anarchy, and civil war.

Could the Union be preserved? Yes, easily; the North had only to will it to accomplish it; to agree to a restoration of the lost equilibrium of equal North-South representation in the Senate, and to cease "agitating" the slavery question. Calhoun had precedent and law on his side of the debate.

However, the North had time and rapid population growth due to industrialization, and the Compromise was passed. With the annexation of Texas, the South had almost reached the limits of farmlands suitable for cotton or other plantations.

The evils of war and political parties

John Calhoun was consistently opposed to the war with Mexico from its very beginning, arguing that an enlarged military effort would only feed the alarming and growing lust of the public for empire regardless of its constitutional dangers, bloat of executive powers, and patronage, and saddle the republic with a soaring debt that would disrupt finances and encourage speculation.

Calhoun feared, moreover, that southern slave owners would be shut out of any conquered Mexican territories.

Many northerners saw the war as a Southern conspiracy to expand slavery; John Calhoun saw a conspiracy of Yankees to destroy the South. By 1847, he decided the Union was threatened by a totally corrupt party system.

He believed that in their lust for office, patronage, and spoils, politicians in the North pandered to the antislavery vote, especially during presidential campaigns, and politicians in the slave states sacrificed southern rights in an effort to placate the northern wings of their parties.

Thus, the essential first step in any successful assertion of Southern rights had to be the jettisoning of all party ties. In 1848-49, Calhoun tried to give substance to his call for Southern unity.

He was the driving force behind the drafting and publication of the "Address of the Southern Delegates in Congress, to Their Constituents." It listed the alleged Northern violations of the constitutional rights of the South, then warned Southern voters to expect forced emancipation of slaves in the near future, followed by their complete subjugation by an unholy alliance of unprincipled northerners and blacks and a South forever reduced to "disorder, anarchy, poverty, misery, and wretchedness."

Only the immediate and unflinching unity of southern whites could prevent such a disaster. Such unity would either bring the North to its senses or lay the foundation for an independent South. But the spirit of union was still strong in the region, and fewer than 40% of the southern congressmen signed the address, and only one Whig.

Southerners believed his warnings and read every political news story from the North as further evidence of the planned destruction of the Southern way of life.

The most notable case was the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln in 1860, which led immediately to the secession of South Carolina, followed by six other cotton states.

They formed the new Confederate States of America, which, in accord with Calhoun's theory, did not have any political parties.

Slavery

John Calhoun was shaped by his own father, Patrick Calhoun, a prosperous backcountry slaveholder who supported the war but opposed the ratification of the federal Constitution. The father was a model of republican virtue who taught his son that one's standing in society depended not merely on one's commitment to the ideal of popular self-government but also on the ownership of a substantial number of slaves.

Flourishing in a world in which slaveholding was a badge of civilization, Calhoun saw little reason to question its morality as an adult; he never visited Europe. Calhoun had seen in his own state how the spread of slavery into the backcountry improved public morals by ridding the countryside of the shiftless poor whites who had once terrorized the law-abiding middle class.

John Calhoun believed that slavery was instilled in the whites who remained a code of honor that blunted the disruptive potential of private gain and fostered the civic-mindedness that lay near the core of the republican creed.

From such a standpoint, the expansion of slavery into the backcountry decreased the likelihood of social conflict and postponed the declension when money would become the only measure of self-worth, as had happened in New England. Calhoun was thus firmly convinced that slavery was the key to the success of the American dream.

On February 6, 1837, John C. Calhoun took the floor of the Senate to declare that slavery was a "positive good." Senator William Rives of Virginia had referred to slavery as an evil that might become a "lesser evil" in some circumstances.

Calhoun believed that conceded too much to the abolitionists:

I take the higher ground. I hold that in the present state of civilization, where two races of different origins, distinguished by color and other physical differences, as well as intellectual, are brought together, the relation now existing in the slaveholding States between the two is, instead of an evil, a good-a positive good. . . . I hold, then, that there never has yet existed a wealthy and civilized society in which one portion of the community did not, in point of fact, live on the labor of the other.

A year later, in the Senate (January 10, 1838), Calhoun repeated this defense of slavery as a "positive good": "Many in the South once believed that it was a moral and political evil; that folly and delusion are gone; we see it now in its true light, and regard it as the safest and stable basis for free institutions in the world."

Calhoun rejected the belief of Southern moderates such as Henry Clay that all Americans could agree on the "opinion and feeling" that slavery was wrong, although they might disagree on the most practicable way to respond to that great wrong.

Calhoun's constitutional ideas acted as a viable alternative to Northern appeals to democracy, majority rule, and natural rights.

Death

John Calhoun died at the Old Brick Capitol boarding house in Washington, D.C., on March 31, 1850, of tuberculosis at the age of 68. The last words attributed to him were, "The South, the poor South!"

He was interred at St. Philip's Churchyard in Charleston, South Carolina. During the Civil War, a group of Calhoun's friends were concerned about the possible desecration of his grave by Federal troops and, during the night, removed his coffin to a hiding place under the stairs of the church.

The next night, his coffin was buried in an unmarked grave near the church, where it remained until 1871, when it was again exhumed and returned to its original place.

After John John Calhoun Calhoun had died, an associate suggested that Senator Thomas Hart Benton give a eulogy in honor of Calhoun on the floor of the Senate. Benton, a devoted Unionist, declined, saying:

"He is not dead, sir-he is not dead. There may be no vitality in his body, but there is in his doctrines.