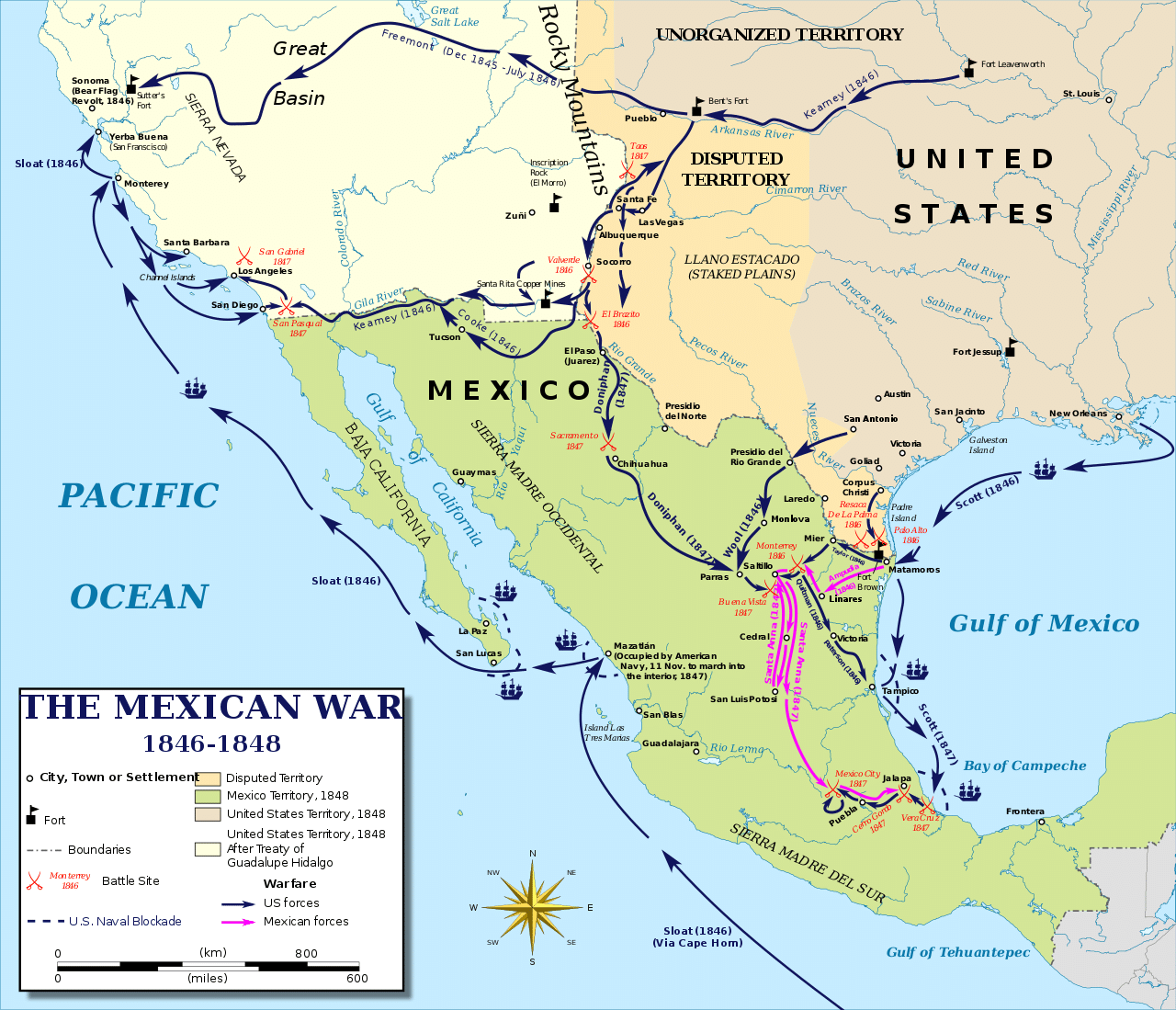

The Mexican–American War was a major war between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848 in response to the U. S. annexation of Texas in 1845.

Pushed by Democrats, especially newly elected President James K. Polk and outgoing President John Tyler, Congress on March 1, 1845, jointly resolved to admit the independent Republic of Texas into the Union as a state.

Whigs (this included then Whig Abraham Lincoln) generally were opposed. Mexico had long warned that annexation meant war, and brushing aside American offers to negotiate, and British offers to mediate, the Mexican government promptly broke off diplomatic relations and sent troops into the disputed region claimed by both Mexico and the Republic of Texas, and now claimed by the United States.

Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to move U.S. Army forces to a point "on or near" the Rio Grande to repel any invasion from Mexico.

Jump to:

Lying in Wait

General Taylor selected a wide sandy plain at the mouth of the Nueces River near the hamlet of Corpus Christi and, beginning July 23, sent most of his 1,500-man force by steamboat from New Orleans. Only his dragoons moved overland via San Antonio. By mid-October, as shipments of regulars continued to come in from all over the country, his forces had swollen to nearly 4,000, including some volunteers from New Orleans. This force constituted nearly 50 percent of the 7,365-strong Regular Army.

A company of Texas Rangers served as the eyes and ears of the Army. For the next six months, tactical drilling, horse breaking, and parades, interspersed with boredom and dissipation, went on at the big camp on the Nueces. Then, in February, Taylor received orders from Washington to advance into disputed territory to the Rio Grande. Negotiations with the Mexican government had broken down.

The march of more than a hundred miles down the coast to the Rio Grande was led by Bvt. Maj. Samuel Ringgold's battery of "flying artillery." It was the last word in mobility, for the cannoneers rode on horseback rather than on limbers and caissons.

Taylor's supply train of 300 ox-drawn wagons brought up the rear. On March 23, the columns came to a road that forked left to Point Isabel, ten miles away on the coast, where Taylor's supply ships were waiting, and led on the right to his destination on the Rio Grande, eighteen miles southwest, opposite the Mexican town of Matamoros. Sending the bulk of his army ahead, Taylor went to Point Isabel to set up his supply base, fill his wagons, and bring forward four 18-lb. siege guns from his ships.

At the boiling brown waters of the Rio Grande opposite Matamoros, Taylor built a strong fort, which he called Fort Texas, and mounted his siege guns. At the same time, he sent messages of peace to the Mexican commander on the opposite bank.

These were countered by threats and warnings, and on April 25, the day after the arrival at Matamoros of General Mariano Arista with two or three thousand additional troops, by open hostilities. The Mexicans crossed the river in some force and attacked a reconnoitering detachment of sixty dragoons under Capt. Seth B. Thornton. They killed eleven men and captured Thornton and the rest, many of whom were wounded.

Taylor reported to President Polk that hostilities had commenced and called on Texas and Louisiana for about 5,000 militiamen. His immediate concern was that his supply base might be captured. Leaving an infantry regiment and a small detachment of artillery at Fort Texas under Maj. Jacob Brown he set off May 1 with the bulk of his forces for Point Isabel, where he stayed nearly a week strengthening his fortifications.

After loading two hundred supply wagons and acquiring two more ox-drawn 18-pounders, he began the return march to Fort Texas with his army of about 2,300 men on the afternoon of May 7. About noon the next day, near a clump of tall trees at a spot called Palo Alto, he saw across the open prairie a long dark line with bayonets and lances glistening in the sun. It was the Mexican Army.

Pre-War Actions

Containing some of the best regular units in the Mexican Army, General Arista's forces, barring the road to Fort Texas, stretched out on a front a mile long and were about 4,000 strong. Taylor, who had placed part of his force in the rear to guard the supply wagons, was outnumbered at least two to one, and in terrain that favored cavalry, Arista's cavalry overwhelmingly outnumbered Taylor's dragoons. On the plus side, for the Americans, their artillery was superior.

Also, among Taylor's junior officers were a number of capable West Point graduates, notably 2d Lt. George Meade and 2d Lt. Ulysses S. Grant, who were to become famous in the Civil War.

On the advice of the young West Pointers on his staff, Taylor emplaced his two 18-lb. iron siege guns in the center of his line and blasted the advancing Mexicans with a canister. His field artillery, bronze 6-lb. guns firing solid shots and 12-lb. howitzers firing shells, in quick-moving attacks threw back Arista's flanks. The Mexicans were using old-fashioned bronze 4-pounders and 8-pounders that fired solid shots and had such short ranges that their fire did little damage.

During the battle, Lieutenant Grant saw their cannonballs striking the ground before they reached the American troops and ricocheting so slowly that the men could dodge them.

During the afternoon, a gunwad set the dry grass afire, causing the battle to be suspended for nearly an hour. After it resumed, the Mexicans fell back rapidly. By nightfall, when both armies went into bivouac, Mexican casualties, caused mostly by cannon fire, numbered 320 killed and 380 wounded. Taylor lost only 9 men killed and 47 wounded. One of the mortally wounded was his brilliant artilleryman, Major Ringgold.

At daybreak, the Americans saw the Mexicans in full retreat. Taylor decided to pursue but did not begin his advance until afternoon, spending the morning erecting defenses around his wagon train, which he intended to leave behind.

About two o’clock, he reached Resaca de la Palma, a dry riverbed about five miles from Palo Alto. There, his scouts reported that the Mexicans had taken advantage of his delay to entrench themselves strongly a short distance down the road in a similar shallow ravine known as Resaca de la Guerra, whose banks formed a natural breastwork. Narrow ponds and thick chaparral protected their flanks.

Taylor sent forward his flying artillery, now commanded by Lt. Randolph Ridgely. Stopped by a Mexican battery, Ridgely sent back for help; Taylor ordered a detachment of dragoons under Capt. Charles A. May. The dragoons overran the Mexican guns but, on their return, were caught in infantry crossfire from the thickets and could not prevent the enemy from recapturing the guns.

American infantrymen later captured the pieces. Dense chaparral prevented Taylor from making full use of his artillery. The battle of Resaca de la Palma was an infantry battle of small-unit actions and close-in, hand-to-hand fighting.

The Mexicans, still demoralized by their defeat at Palo Alto and lacking effective leadership, gave up the fight and fled toward Matamoros. Their losses at Resaca de la Palma were later officially reported as 547 but may have been greater.

The Americans lost 33 killed and 89 wounded. In the meantime, Fort Texas had been attacked by the Mexicans on May 3 and had withstood a two-day siege with the loss of only two men, one of them its commander, for whom the fort was later renamed Fort Brown. Lieutenant Grant saw their cannonballs striking the ground before they reached the American troops and ricocheting so slowly that the men could dodge them.

The panic-stricken Mexicans fleeing to Matamoros crossed the Rio Grande as best they could, some by boats, some by swimming. Many drowned; others were killed by the guns of Fort Texas. If Taylor's regulars, flush with victory and yelling as they pursued the enemy, had been able to catch up with Arista, they could probably have taken his demoralized army, complete with guns and ammunition. But Taylor had failed to make any provision for crossing the Rio Grande.

He blamed the War Department's failure to provide him with pontoon equipment (developed during the Second Seminole War), which he had requested while he was still at Corpus Christi. Since that time, however, he had done nothing to acquire bridge materials or boats, although the West Pointers had urged him to do so. Lieutenant Meade reported that "the old gentleman would never listen or give it a moment’s attention."

Not until May 18, after Taylor had brought up some boats from Point Isabel, was he able to cross into Matamoros. By that time, Arista's army had pulled back into the interior to rest, recoup, and fight another day.

Polk Declares War

On the evening of May 9, the day of the battle of Resaca de la Palma, President Polk received a message from the War Department that informed him of the attack on Captain Thornton's detachment on April 25. Polk, already convinced by the breakdown in negotiations with Mexico that war was justified, immediately drafted a message declaring that a state of war existed between the United States and Mexico. Congress passed the declaration, and Polk signed it on May 13.

Congress then appropriated $10 million and substantially increased the strength of the Army. (After the Second Seminole War, the authorized strength had been cut from 12,500 to 8,500. This had been done by reducing the rank and file strength of the regiments instead of eliminating units, thus firmly establishing the principle of an expansible Army.)

Congress raised the authorized enlisted strength of a company from 64 to 100 men, bringing the rank and file up to 15,540, and added a regiment of mounted riflemen and a company of sappers, miners, and pontoniers (engineers for pontoon bridges). Also, the President was authorized to call for 50,000 volunteers for a term of one year or the duration of the war.

The President went into the war with one object clearly in view: to seize all of Mexico north of the Rio Grande and the Gila River and westward to the Pacific, after his discussions with War of 1812 veteran Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott, the outlines of a three-pronged thrust emerged. General Taylor was to advance westward from Matamoros to the city of Monterrey, the key to further progress in northern Mexico. A second expedition under Brig.

Gen. John E. Wool was to move from San Antonio to the remote city of Chihuahua in the west, an expedition later directed southward to Saltillo near Monterrey. A third prong under Col. Stephen W. Kearny was to start at Fort Leavenworth, capture Santa Fe, and ultimately continue to San Diego on the coast of California. Part of Kearny's forces under volunteer Col. Alexander W. Doniphan later marched south through El Paso to Chihuahua. Although small in numbers, only 1,600 strong, Kearny's and Doniphan's forces posed strategic threats to Mexico's northern states.

Polk was counting on "a brisk and a short war"; not until July did he and his Secretary of War, William L. Marcy, even begin to consider the possibility of an advance on Mexico City by landing a force on the Gulf of Mexico near Vera Cruz. General Scott was not so optimistic. He was more aware of the problems of supply, transportation, communications, and mobilization involved in operations against Mexico, a country with a population of 7 million and an army of about 30,000, many with experience gained by twenty years of intermittent revolution.

Scott's preparations seemed too slow to Polk. Ostensibly for that reason, but also because success in the field might make the politically motivated Scott a powerful contender for the Presidency, Polk decided not to give him command of the forces in the field. When news came of the victories at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma, Polk promoted Zachary Taylor to the brevet rank of major general and gave him command of the army in Mexico, risking the possibility that Taylor might also use a victory to vault into high political office.

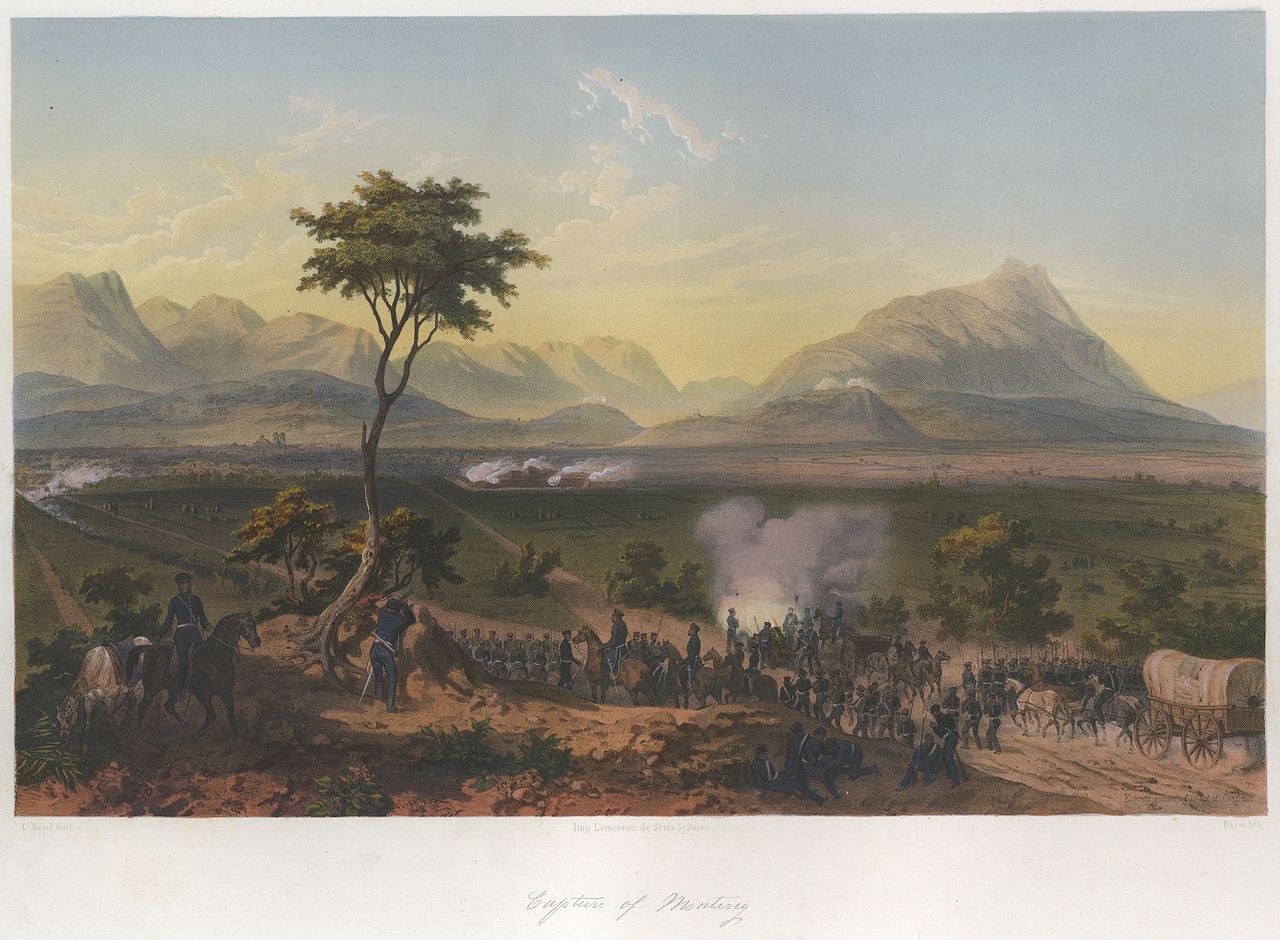

The Monterrey Campaign

Taylor's plan was to move on Monterrey with about 6,000 men via Camargo, a small town on the San Juan River, a tributary of the Rio Grande about 130 miles upriver. From Camargo, where he intended to set up a supply base, a road led southwest about 125 miles to Monterrey in the foothills of the Sierra Madres.

His troops were to march overland to Camargo, his supplies to come by steamboat up the Rio Grande. But he could not move immediately because he lacked transportation, partly because of his failure to requisition in time and partly because of the effort required to build more wagons in the United States and to collect shallow-draft steamboats at river towns on the Mississippi and Ohio and send them across the Gulf of Mexico.

Ten steamboats were in operation at the end of July, but wagons did not begin arriving until November after the campaign was over. To supplement his wagon train, reduced to 175, Taylor had to rely on 1,500 Mexican pack mules and a few native oxcarts.

In the manpower, Taylor had an embarrassment of riches. May saw the arrival of the first of the three-month militia he had requested on April 26 from the governors of Texas and Louisiana.

With them came thousands of additional six-month volunteers from neighboring states recruited by Bvt. Maj. Gen. Edmund P. Gaines, commander of the Department of the West, on his own initiative, a repetition of his impulsive actions during the Second Seminole War.

More than 8,000 of these short-term volunteers were sent before Gaines was censured by a court-martial for his unauthorized and illegal recruiting practices and transferred to New York to command the Department of the East. Very few of his recruits had agreed to serve for twelve months. All the rest were sent home without performing any service; in the meantime, they had to be fed, sheltered, and transported. In June, the volunteers authorized by Congress began pouring into Point Isabel and were quartered in a string of camps along the Rio Grande as far as Matamoros.

By August, Taylor had a force of about 15,000 men at Camargo, an unhealthy town deep in mud from recent heavy rains and sweltering under heat that rose as high as 112 degrees. Many of the volunteers became ill, and more than half were left behind when Taylor advanced toward Monterrey at the end of August with 3,080 regulars and 3,150 volunteers. The regulars with a few volunteers were organized into the First and Second Divisions, the volunteers mainly into a Field Division, though two regiments of mounted Texans were thought of as the Texas Division.

More than a fourth of the troops were mounted, among them the First Mississippi Rifle Regiment under a West Point graduate recently elected to Congress, Col. Jefferson Davis. The mounted riflemen had percussion rifles; the infantrymen were armed with flintlock smooth-bore muskets. Taylor placed great reliance on the bayonet. He had a low opinion of artillery and, though warned that field pieces were not effective against the stone houses of Mexican towns, he had, in addition to his four field batteries, only two 24-lb. howitzers and one 10-inch mortar, the latter his only real siege piece.

By September 19, Taylor's army reached Monterrey, a well-fortified city in a pass of the Sierra Madres leading to the city of Saltillo. Monterrey was strongly defended by more than 7,000 Mexicans with better artillery than the Mexicans had had at Palo Alto, new British 9- and 12-lb. guns. Taylor encamped on the outskirts of Monterrey, sent out reconnoitering parties accompanied by engineers, and on September 20 began his attack. On the north, the city was protected by a formidable citadel, on the south by a river, and it was ringed with forts.

Taylor sent one of his regular divisions, with 400 Texas Rangers in advance, around to the west to cut off the road to Saltillo; and after a miserable night of drenching rain, it accomplished its mission the next day, September 21, though at the cost of 394 dead or wounded, a high proportion of the officers. Taylor placed his heavy howitzers and one mortar in position to fire on the citadel and sent the remainder of his forces to close in from the eastern outskirts of the town.

By the third day, both attacks were driving into the city proper, the men battering down doors of the stone and adobe houses with planks, tossing lighted shells through apertures, and advancing from house to house rather than from street to street, tactics that were to be used a century later by American troops in Italian and German towns.

The climax came when the 10-inch mortar was brought up to lob shells on the great plaza into which the Mexican troops had been driven. On September 24, the Mexican commander offered to surrender on condition that his troops be allowed to withdraw unimpeded and that an eight-week armistice go into effect.

Taylor agreed to the proposal. He had lost some 800 men to battle casualties and sickness, besides quantities of arms and ammunition, and he was about 125 miles from his base. Moreover, he believed that magnanimity would advance the negotiations for peace that had begun when President Polk allowed General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna to return to Mexico from exile in Havana to exert his influence in favor of a treaty.

When Polk received the news from Monterrey by courier on October 11, he condemned Taylor for allowing the Mexican Army to escape and ordered the armistice terminated. On November 13, Taylor sent a thousand men 68 miles southwest to occupy Saltillo, an important road center commanding the only road to Mexico City from the north that was practicable for wagons and guns. Saltillo also commanded the road west to Chihuahua and east to Victoria, the capital of Tamaulipas, the province that contained Tampico, the second-largest Mexican port on the gulf.

The U.S. Navy captured Tampico on November 15. On the road to Chihuahua was the town of Parras, where General Wool's expedition of about 2,500 men arrived early in December after a remarkable march from San Antonio. On the way, Wool had learned that the Mexican troops holding Chihuahua had abandoned it; accordingly, he joined Taylor's main army. Taylor thus acquired a valuable West Point–trained engineer officer who had been scouting with Wool, Capt. Robert E. Lee.

Taylor was planning to establish a strong defensive line, Parras-Saltillo-Monterrey-Victoria, when he learned that most of his troops would have to be dispatched to join General Scott's invasion of Mexico at Vera Cruz, an operation that had been decided upon in Washington in mid-November. Scott arrived in Mexico in late December.

He proceeded to Camargo and detached almost all of Taylor's regulars, about 4,000, and an equal number of volunteers, ordering them to rendezvous at Tampico and at the mouth of the Brazos River in Texas. Taylor, left with fewer than 7,000 men, all volunteers except two squadrons of dragoons and a small force of artillery, was ordered to evacuate Saltillo and go on the defensive at Monterrey.

Enraged, Taylor attributed Scott's motive to politics. Hurrying back to Monterrey from Victoria, he decided to interpret Scott's orders as "advice" rather than as an order. Instead of retiring his forces to Monterrey, he moved 4,650 of his troops (leaving garrisons at Monterrey and Saltillo) to a point eighteen miles south of Saltillo, near the hacienda of Agua Nueva.

This move brought him almost eleven miles closer to San Luis Potosí, 200 miles to the south, where General Santa Anna was assembling an army of 20,000. Most of the 200 miles were desert, which Taylor considered impassable by any army; moreover, both he and Scott believed that Santa Anna would make his main effort against Scott's landing at Vera Cruz, the news of which had leaked to the newspapers. On February 8, 1847, Taylor wrote a friend, "I have no fears."

At the time he wrote, Santa Anna was already on the march north toward Saltillo. Stung by newspaper reports that he had sold out to the Americans, Santa Anna risked a daring strategic move. He was determined to win a quick victory, and he thought he saw his opportunity when his troops brought him a copy of Scott's order depleting Taylor's forces, found on the body of a messenger they had ambushed and killed.

Leading his army across the barren country through heat, snow, and rain, by February 19, Santa Anna had 15,000 men at a hacienda at the edge of the desert, only thirty-five miles from Agua Nueva. One of the hardest-fought battles of the Mexican War was about to begin.

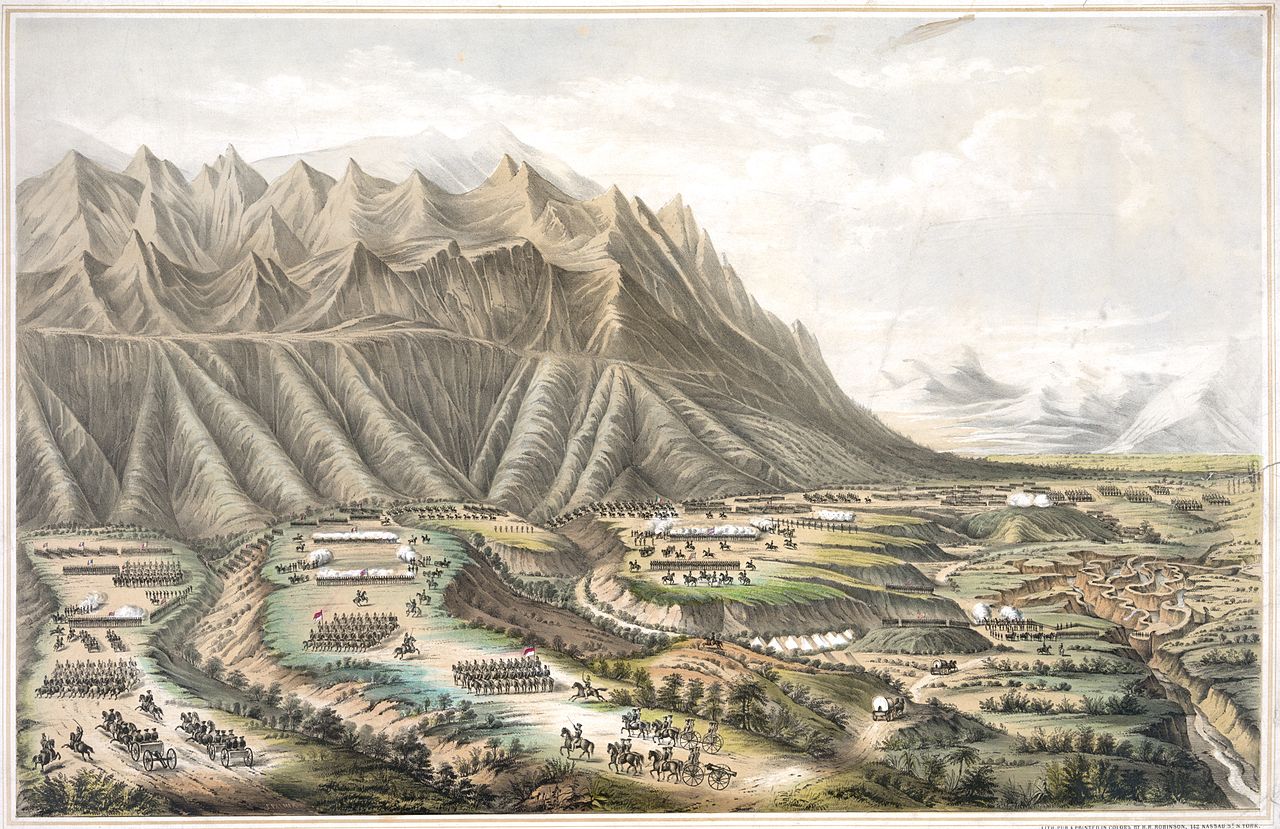

Battle of Buena Vista

On the morning of February 21, scouts brought word to General Taylor that a great Mexican army was advancing, preceded by a large body of cavalry swinging east to block the road between Agua Nueva and Saltillo. That afternoon, Taylor withdrew his forces up the Saltillo road about 15 miles to a better defensive position near the hacienda Buena Vista, a few miles south of Saltillo.

There, a mile south of the clay-roofed ranch buildings, mountain spurs came down to the road on the east, the longest and highest known as La Angostura; between them was a wide plateau cut by two deep ravines. West of the road was a network of gullies backed by a line of high hills. Leaving General Wool to deploy the troops, Taylor rode off to Saltillo to look after his defenses there.

By the next morning, Washington's Birthday (the password was "Honor to Washington"), the little American army of fewer than 5,000 troops, most of them green volunteers, was in position to meet a Mexican army more than three times its size. The American main body was east of the road near La Angostura, where artillery had been emplaced, commanding the road.

West of the road, the gullies were thought to be sufficient protection.

Santa Anna arrived with his vanguard around eleven o’clock. Disliking the terrain, which by no means favored cavalry (the best units in his army), he sent a demand for surrender to Taylor, who had returned from Saltillo. Taylor refused.

Then Santa Anna planted artillery on the road and the high ground east of it and sent a force of light infantry around the foot of the mountains south of the plateau. About three o’clock, a shell from a Mexican howitzer on the road gave the signal for combat, but the rest of the day was consumed mainly in jockeying for position on the mountain spurs, a competition in which the Mexicans came off best, and the placing of American infantry and artillery well forward on the plateau.

After a threatening movement on the Mexican left, Taylor sent a Kentucky regiment with two guns of Maj. Braxton Bragg's Regular Army battery to the high hills west of the road, but no attack occurred there. Toward evening, Taylor returned to Saltillo, accompanied by the First Mississippi Rifles and a detachment of dragoons. At nightfall, his soldiers, shaken by the size and splendid appearance of the Mexican army, got what sleep they could.

The next day, February 23, the battle opened in earnest at dawn. Santa Anna sent a division up the road toward La Angostura, at the head of the defile; but American artillery and infantrymen quickly broke it, and no further action occurred in that sector.

The strongest assault took place on the plateau, well to the east, where Santa Anna launched two divisions backed by a strong battery at the head of the southernmost ravine. The Americans, farthest forward, part of an Indiana regiment supported by three cannons, held off the assault for half an hour; then, their commander gave them the order to retreat.

They broke and ran and were joined in their flight by adjoining regiments. Some of the men ran all the way back to Buena Vista, where they fired at pursuing Mexican cavalrymen from behind the hacienda walls.

About nine o’clock that morning, when the battle had become almost a rout, General Taylor arrived from Saltillo with his dragoons, Colonel Davis’ Mississippi Rifles, and some men of the Indiana regiment whom he had rallied on the way.

They fell upon the Mexican cavalry that had been trying to outflank the Americans north of the plateau. In the meantime, Bragg's artillery had come over from the hills west of the road, and the Kentucky regiment also crossed the road to join in the fight. A deafening thunderstorm of rain and hail broke early in the afternoon, but the Americans in the north field continued to force the Mexicans back.

Just when victory for the Americans seemed in sight, Santa Anna threw an entire division of fresh troops, his reserves, against the plateau. Rising from the broad ravine where they had been hidden, the Mexicans of the left column fell upon three regiments, two Illinois and one Kentucky, and forced them back to the road with withering fire while the right stormed the weak American center.

They seemed about to turn the tide of battle when down from the north field galloped two batteries, followed by the Mississippians and Indianans led by Jefferson Davis, wounded but still in the saddle. They fell upon the Mexicans’ right and rear and forced them back into the ravine. The Mexicans’ left, pursuing the Illinois and Kentucky regiments up the road, was cut to pieces by the American battery at La Angostura.

That night, Santa Anna, having lost 1,500 to 2,000 men killed and wounded, retreated toward San Luis Potosí. The Americans, with 264 men killed, 450 wounded, and 26 missing, had won the battle. A great share of the credit belonged to the artillery; without it, as General Wool said in his report, the army could not have stood "for a single hour." Moving with almost the speed of cavalry, the batteries served as rallying points for the infantry.

The fighting spirit of the volunteers and the able and courageous leadership of the officers were beyond praise. Perhaps the greatest contribution to the victory had been Zachary Taylor himself. Stationed all day conspicuously in the center of the battle, hunched on his horse "Old Whitey" with one leg hooked over the pommel of his saddle, disregarding two Mexican bullets that ripped through his coat, and occasionally rising in his stirrups to shout encouragement, he was an inspiration to his men, who swore by him. Under such a leader, they felt that defeat was impossible.

Taylor knew little of the art of war. He was careless in preparing for battle and neglected intelligence; he often misunderstood the intention of the enemy and underestimated the enemy's strength. But he possessed a high degree of physical and moral courage, which, according to Jomini, are the most essential qualities for a general.

He constantly sought to regain the initiative by attacking the enemy. He and his subordinates used the principle of the offensive to turn the tide of the battle several times by the end of the long day.

Buena Vista ended any further Mexican threat against the lower Rio Grande. On the Pacific coast, Colonel Kearny led one of the most extraordinary marches in American history across deserts and rugged mountains. His force left Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, on June 2, 1846, and headed for California via the Santa Fe Trail. After capturing Santa Fe without firing a shot on August 18, he continued his march to the west.

Convinced through an erroneous intelligence report from "Kit" Carson that California had already fallen to U.S. forces, Kearny left most of his forces in Santa Fe and continued on to California with a single dragoon company. He marched his men nearly 1,000 miles over snow-capped mountains and through desolate, snake-infested deserts. After finally reaching California on December 4, the exhausted dragoons were reinforced by thirty-five marines.

Learning that the Californios, or native Mexican population, were in revolt, Kearny attacked a force of seventy-five Californios at San Pascual two days later to assist the beleaguered American garrison at San Diego.

Kearny's dragoons took heavy losses against the skilled Californio lancers, but they withdrew before crushing Kearny's force. After relieving the garrison at San Diego, Kearny joined other U.S. forces in the region to recapture Los Angeles. On January 8, 1847, a joint force of sailors, marines, and dragoons under Kearny engaged 350 Californios at the San Gabriel River, south of Los Angeles. After a brief but hard-fought battle, the Californios withdrew and formally capitulated on January 13.

Early in February 1847, a force of Missouri volunteers detached from Kearny's command and led by Colonel Doniphan had set out from Santa Fe to pacify the region of the upper Rio Grande. Crossing the river at El Paso, they defeated a large force of Mexicans, mostly militia, at Chihuahua less than a week after Taylor's victory at Buena Vista. Thus, by March 1847, America's hold on Mexico's northern provinces was secure. All that remained to complete the victory was the capture of Mexico City.

Landing on Vera Cruz

From a rendezvous at Lobos Island almost fifty miles south of Tampico, General Scott's force of 13,660 men, of whom 5,741 were regulars, set sail on March 2, 1847, for the landing near Vera Cruz. On March 5, the transports were off the coast of their target, where they met a U.S. naval squadron blockading the city.

In a small boat, Scott, his commanders, and a party of officers, including Lee, Meade, Joseph E. Johnston, and P. G. T. Beauregard, ran close inshore to reconnoiter and were almost hit by a shell fired from the island fortress of San Juan de Ulua opposite Vera Cruz. That shell might have changed the course of the Mexican War and the Civil War as well.

Scott chose for the landing a beach nearly three miles south of the city, beyond the range of the Mexican guns. On the evening of March 9, in four hours, more than 10,000 men went ashore in landing craft, sixty-five heavy surf boats that had been towed to the spot by steamers.

The troops proceeded inland over the sand hills with little opposition from the Mexican force of 4,300 behind the city's walls. The landing of artillery, stores, and horses, the last thrown overboard and forced to swim for shore, was slowed by a norther that sprang up on March 12 and blew violently for four days, but by March 22, seven 10-inch mortars had been dragged inland and emplaced about half a mile south of Vera Cruz. That afternoon, the bombardment began.

Town and fort replied, and it was soon apparent that the mortars were ineffective. Scott found himself compelled to ask for naval guns from the commander of the naval force, Commodore Matthew C. Perry. The six naval guns, three 32-pounders firing shots, and three 8-inch shell guns soon breached the walls and demoralized the defenders. On March 27, 1847, Vera Cruz capitulated.

This landing, largely unknown, was the first major amphibious operation in American history. Unfortunately, the batteries that opened fire on March 22 wreaked havoc on civilian structures in the city, and many innocent people died.

Scott's next objective was Jalapa, a city in the highlands about seventy- four miles from Vera Cruz on the national highway leading to Mexico City. Because on the coast, the yellow fever season was approaching, Scott was anxious to move forward to the uplands at once, but not until April 8 was he able to collect enough pack mules and wagons for the advance. The first elements, under Bvt. Maj. Gen. David E. Twiggs set out with two batteries. One was equipped with 24-lb. guns, 8-inch howitzers, and 10-inch mortars.

The other was a new type of battery equipped with mountain howitzers and rockets, officered and manned by the Ordnance Corps. The rocket section, mainly armed with the Congreve, carried for service tests a new rocket, the Hale, which depended for stability not on a stick but on vents in the rear, which also gave it a spin like that of an artillery projectile. The rockets were fired from troughs mounted on portable stands.

In addition to his two batteries, General Twiggs had a squadron of dragoons, in all about 2,600 men. He advanced confidently, though Scott had warned him that a substantial army commanded by Santa Anna lay somewhere ahead. On April 11, after Twiggs had gone about thirty miles, his scouts brought word that Mexican guns commanded a pass near the hamlet of Cerro Gordo.

Battle of Cerro Gordo

Near Cerro Gordo, the national highway ran through a rocky defile. On the left of the approaching Americans, Santa Anna, with about 12,000 men, had emplaced batteries on mountain spurs, and on the right of the Americans, farther down the road, his guns were emplaced on a high hill, El Telegrafo. He thus had a firm command of the national highway. The only means he thought Scott had of bringing up his artillery.

Fortunately for Twiggs, advancing on the morning of April 12, the Mexican gunners opened fire before he was within range, and he was able to pull his forces back. Two days later, Scott arrived with reinforcements, bringing his army up to 8,500. A reconnaissance by Captain Lee showed that the rough country to the right of El Telegrafo, which Santa Anna had considered impassable, could be traversed to enable the Americans to cut in on the Mexican rear.

The troops hewed a path through forest and brush; when they came to ravines, they lowered the heavy siege artillery by ropes to the bottom, then hoisted it up the other side. By April 17, they were able to occupy a hill to the right of El Telegrafo, where they sited the rocket battery. Early on the morning of April 18, the battle began.

Though Santa Anna, by then forewarned, had been able to plant guns to protect his flank, he could not withstand the American onslaught. The Mexicans broke and fled into the mountains. By noon, Scott's army had won a smashing victory at a cost of only 417 casualties, including 64 dead. Santa Anna's losses were estimated at more than a thousand.

Scott moved the next morning to Jalapa. The way seemed open to Mexico City, only 170 miles away. But now he faced a serious loss in manpower. The term of enlistment of seven of his volunteer regiments was about to expire, and only a handful agreed to reenlist. The men had to be sent home at once to minimize the danger of yellow fever when they passed through Vera Cruz. The departure of the volunteers, along with wounds and sickness among the remaining men, reduced the army to 5,820 effective.

In May, Scott pushed forward cautiously to Puebla, then the second-largest city in Mexico. Its citizens were hostile to Santa Anna and had lost hope of winning the war. It capitulated without resistance on May 15 to an advance party under General Worth.

Scott stayed there until the beginning of August, awaiting reinforcements from Vera Cruz (which by mid-July more than doubled his forces) and awaiting the outcome of peace negotiations then underway. A State Department emissary, Nicholas P. Trist, had arrived on the scene and made contact with Santa Anna through a British agent in Mexico City.

Trist learned that Santa Anna, elected President of Mexico for the second time, would discuss peace terms for $10,000 down and $1 million to be paid when a treaty was ratified. After receiving the down payment through the intermediary, however, Santa Anna made it known that he could not prevail upon the Mexican Congress to repeal a law it had passed after the battle of Cerro Gordo that made it high treason for any official to treat with the Americans.

It was clear that Scott would have to move closer to the capital of Mexico before Santa Anna would seriously consider peace terms.

Final Months of the Mexican War

For the advance on Mexico City, Scott had about 10,000 men. He had none to spare to protect the road from Vera Cruz to Puebla; therefore, his decision to move forward was daring. It meant that he had abandoned his line of communications or, as he phrased it, "thrown away the scabbard."

On August 7, Scott moved off with the lead division, followed at a day's march by three divisions with a three-mile-long train of white-topped supply wagons bringing up the rear. Meeting no opposition, a sign that Santa Anna had withdrawn to defend Mexico City, Scott, by August 10, was at Ayolta on a high plateau fourteen miles from the city.

The direct road ahead, entering the capital on the east, was barred by strongly fortified positions. Scott, therefore, decided to take the city from the west by a wide flanking movement to the south, using a narrow muddy road that passed between the southern shores of two lakes and the mountains and skirted a fifteen-mile-wide lava bed, the Pedregal, before it turned north and went over a bridge at Churubusco to the western gates of Mexico City.

The Pedregal, like the terrain around El Telegrafo, had been considered impassable, but Captain Lee again made a way through. He found a mule path across its southwestern tip that came out at the village of Contreras. Scott sent a force under Bvt. Maj. Gen. Gideon J. Pillow to work on the road, supported by Twiggs’ division and some light artillery. They came under heavy fire from a Mexican force under General Gabriel Valencia.

Pillow, manhandling his guns to a high position, attacked on August 19, but his light artillery was no match for Valencia's 68-lb. howitzer, nor his men for the reinforcements Santa Anna brought to the scene. American reinforcements made a night march in pouring rain through a gully the engineers had found through the Pedregal to fall upon the Mexicans’ rear on the morning of August 20, simultaneously with an attack from the front.

In seventeen minutes, the battle of Contreras was won, with a loss to Scott of only 60 killed or wounded; the Mexicans lost 700 dead and 800 captured, including 4 generals.

Scott ordered an immediate pursuit, but Santa Anna was able to gather his forces for a stand at Churubusco, where he placed a strong fortification before the town at the bridge and converted a thick-walled stone church and a massive stone convent into fortresses.

When the first American troops rode up around noon, they were met by heavy musket and cannon fire. The Mexicans fought as never before; not until midafternoon could Scott's troops make any progress. At last, the fire of the Mexicans slackened, partly because they were running out of ammunition, and the Americans won the day, a day that Santa Anna admitted had cost him one-third of his forces.

About 4,000 Mexicans had been killed or wounded, not counting the many missing and captured. The battle had also been costly for Scott, who had 155 men killed and 876 wounded, approximately 12 percent of his effective force.

The victory at Churubusco brought an offer from Santa Anna to reopen negotiations. Scott proposed a short armistice, and Santa Anna quickly agreed. For two weeks, Trist and representatives of the Mexican government discussed terms until it became clear that the Mexicans would not accept what Trist had to offer and were merely using the armistice as a breathing spell. On September 6, Scott halted the discussions and prepared to assault Mexico City.

Though refreshed by two weeks of rest, his forces now numbered only about 8,000. Santa Anna was reputed to have more than 15,000 and had taken advantage of the respite to strengthen the defenses of the city. And ahead on a high hill above the plain was the Castle of Chapultepec guarding the western approaches.

Scott's first objective, about half a mile west of Chapultepec, was a range of low stone buildings containing a cannon foundry known as El Molino del Rey. It was seized on September 8, though at heavy cost from unexpected resistance.

At eight o’clock on the morning of September 13, after a barrage from the 24-lb. guns, Scott launched a three-pronged attack over the causeways leading to Chapultepec and up the rugged slopes. Against a hail of Mexican projectiles from above, his determined troops rapidly gained the summit, though they were delayed at the moat waiting for scaling ladders to come up.

By half past nine o’clock, the Americans were overrunning the castle despite a valiant but doomed defense by brave young Mexican cadets. Scarcely pausing, they pressed on to Mexico City by the two routes available and, by nightfall, held two gates to the city. Exhausted and depleted by the 800 casualties suffered that day, the troops still had to face house-to-house fighting; but at dawn the next day, September 14, the city surrendered.

Throughout the campaign from Vera Cruz to Mexico City, General Scott displayed not only dauntless personal courage and fine qualities of leadership but also great skill in applying the principles of war. In preparing for battle, he would order his engineers to make a thorough reconnaissance of the enemy's position and the surrounding terrain.

He was thus able to execute brilliant flanking movements over terrain that the enemy had considered impassable, notably at Cerro Gordo and the Pedregal, the latter a fine illustration of the principle of surprise. Scott also knew when to violate the principles of warfare, as he had done at Puebla when he deliberately severed his line of communications. Able to think beyond mere tactical maneuver, Scott was perhaps the finest strategic thinker in the American Army in the first half of the nineteenth century.

"He sees everything and counts the cost of every measure," said Captain Lee.

Scott, for his part, ascribed his quick victory over Mexico, won without the loss of any battle, to the West Pointers in his army, Lee, Grant, and many others. As for the troops, the trained and disciplined regulars had come off somewhat better than the volunteers, but the army, on the whole, had fought well. Scott had seen to it that the men fought at the right time and place.

Grant summed it up: "Credit is due to the troops engaged, it is true, but the plans and strategy were the general’s."

Occupation of Mexico City

For two months, the main responsible administration in Mexico City was the American military government under Scott. The collection of revenues, suppression of disorder, administration of justice, and all the details of governing were in the hands of the Army.

It has been said that some Mexicans believed that Scott's administration of their city was more efficient and respectful of Mexican property than their own government's. It was an instructive lesson in the value of a careful and relatively enlightened occupation policy. Mexicans organized an interim government with which Commissioner Trist could negotiate a peace treaty, but some dispatches arrived from Washington instructing Trist to return to the United States and ordering Scott to resume the war.

Knowing that the Mexicans were now sincerely desirous of ending the war and realizing that the government in Washington was unaware of the situation, both Trist and Scott decided to continue the negotiations.

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

On February 2, 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed. The U.S. Senate ratified it on March 10, but powerful opposition developed in Mexico. Not until May 30 were ratifications exchanged by the two governments. Preparations began immediately to evacuate American troops from Mexico. On June 12, the occupation troops marched out of Mexico City; on August 1, 1848, the last American soldiers stepped aboard their transports at Vera Cruz and quit Mexican soil.

By the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the United States agreed to pay Mexico $15 million and to assume the unpaid claims by Americans against Mexico. In return, Mexico recognized the Rio Grande as the boundary of Texas and ceded New Mexico (including the present states of Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Nevada, a small corner of present-day Wyoming, and the western and southern portions of Colorado) and Upper California (the present state of California) to the United States. Mexico lost almost half of its land area to the United States by the terms of the treaty.

President Polk had completed one of his goals in stretching American borders from Sea to Shining Sea.

Impact of the Mexican-American War in the United States

After the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, the Americans returned home victorious. They had established themselves as the dominate power in North and South America and had expanded their borders.

New Heroes and political figures rose in popularity, and a new nationalism would spread.

Mexican Cession

Mexico ceded vast amounts of land to the north (what would become Texas, California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, and parts of Wyoming and Colorado) for $15 million that was not completely paid.

War Heroes

General Taylor, nicknamed "Old Rough and Ready," used his popularity to win the Presidency in 1848, despite Polk's efforts to prevent such an election. Other generals would also run for president, including the Republican Party's first candidate and abolitionist, John C. Frémont.

The war also provided experience for the men who would be leaders during the soon-to-come American Civil War, including Ambrose Burnside, Robert E. Lee, Winfield Scott, James Longstreet, Ulysses S. Grant, "Stonewall" Jackson, George McClellan, Jefferson Davis, George Meade

Four teenage Mexican cadets (the youngest of whom was thirteen years old) and their 20-year-old lieutenant squadron leader fought to the death to defend their city. El Día de Los Niños Héroes de Chapultepec (Day of the Boy Heroes of Chapultepec) is celebrated every September 13 in Mexico, the anniversary of the battle, and honors the bravery of the boys.