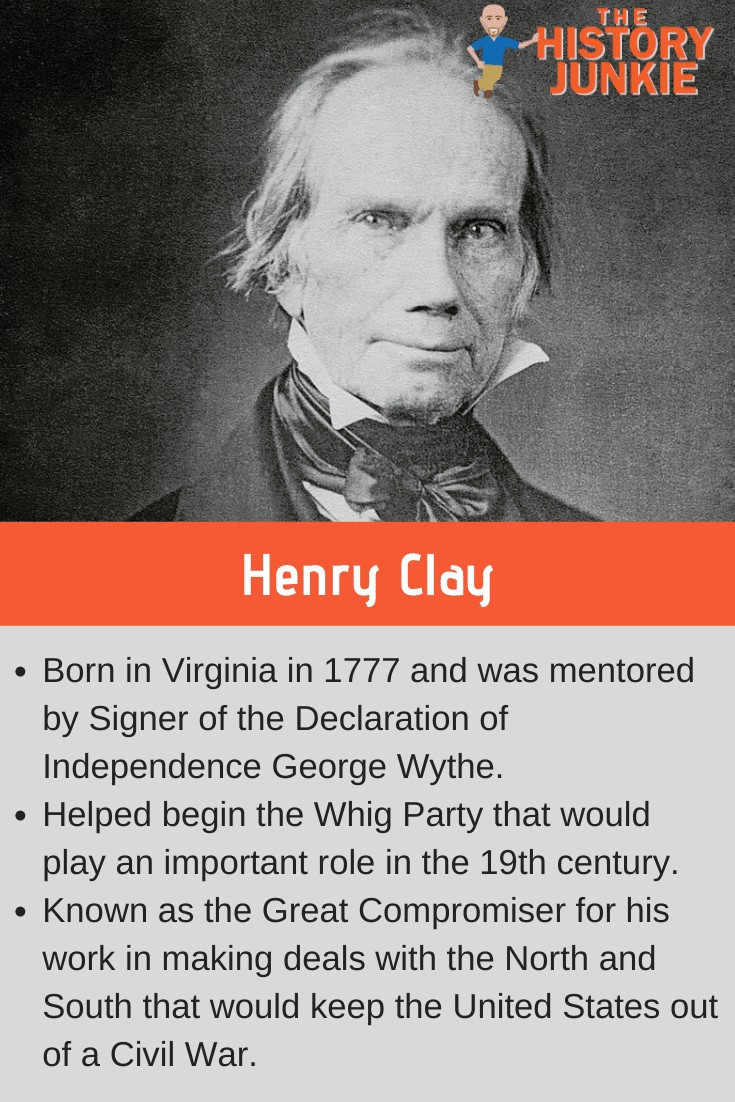

Henry Clay was a leading American politician in the Second Party System and leader of the Whig Party.

He ran and lost three times for President of the United States and is best known for brokering compromises between North and South that held the Union together.

Early Life and Career

His father, a Baptist minister, died when Clay was four; the boy was limited to three years of country schooling. In 1791, when his mother remarried, the family moved to Richmond, where Clay spent a year clerking in a store and then became a copyist for the High Court of Chancery.

He later became secretary and protege of Chancellor George Wythe, the first professor of law in America and a co-author of the Constitution. During 1796, Clay studied law with the attorney general of Virginia, and in 1797 was admitted to the bar.

Although well-connected in Richmond, he decided to move west, where opportunities seemed greater. In 1803, he moved to the growing city of Lexington, Kentucky, the center of the rich bluegrass region with an economy based on horses, hemp, and tobacco farming.

Clay soon won recognition as a criminal lawyer and specialist in land cases; he became wealthy from fees, business operations, and land speculation.

His marriage in April 1799 to Lucretia Hart united him with a prominent family. Clay had a warm, likable personality.

He enjoyed much success at his plantation in Ashland, Kentucky. He introduced Herefords into Kentucky from England and improved the strains of mules. He also bred some of the finest racehorses.

Early Political Career

Clay's political base was not the whole of Kentucky but the bluegrass region. Lexington, the center of the bluegrass, was the major metropolis west of the Alleghenies. The town was surpassed by Louisville, and Clay turned to help the hemp industry.

The hemp growers and rope makers sought protective tariffs on cotton bagging and ropes; the market was the lower South, which insisted upon free trade.

Clay had an unusually long legislative career, serving in the state legislature, in the U.S. Senate, and U.S. House. His name seems to always be somewhere in the mix during the early-mid 19th century.

He was a leader of the Democratic-Republican Party until it collapsed in the mid-1820s. He tried to create the "National Republican Party" and then threw his energies into a new national Whig party.

War of 1812 and Beyond

Clay won election to the House of Representatives, taking his seat in 1811. His personality and skill in oratory had given him authority in Washington; Clay was promptly elected speaker, and his unprecedented energy and competence gave the office a new significance. He was elected to the post six times, never meeting serious opposition.

Clay, in 1811, became the leader of the "War Hawks," a combination of Westerners and Southerners that included Felix Grundy of Kentucky and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina.

Displaying aggressive nationalism at a time when Britain and France were at war, they were outraged by Great Britain's refusal to permit American trade with France and its impressment of American seamen into the British navy.

Kentuckians resented what it considered British influence among western Indians, which turned to massacre settlers on the American frontiersmen. Clay boasted that the Kentucky militia alone could seize Montreal and Upper Canada and so settle all frontier problems.

As speaker of the House, he appointed "War Hawks" to key committees and supported President James Madison demands for war with Great Britain. This would lead to the United States entering the War of 1812 against the British.

The House and Senate declared war in June after stormy debates, which showed New England strongly opposed the War of 1812.

During the ensuing hostilities, which were made more difficult by the noncooperation of New England Federalists, who felt that Madison had pushed an unwanted war on them, Clay's appeals for patriotism and fortitude were a source of strength to the administration.

In 1814, he was at Ghent with the American delegation, which negotiated the Treaty of Ghent, signed on Christmas eve.

His shrewd surmise that the British would accept moderate terms despite their land victories served the United States better than John Quincy Adams' readiness to give the British free navigation of the Mississippi River in exchange for the right of New Englanders to fish in Canadian waters.

American System

Clay resumed the speakership of the House of Representatives and, looking toward the presidency, began to develop his famous "American System." It called for national defense, construction of roads and canals with federal aid, protection of home industry through duties on foreign imports, and establishment of a second Bank of the United States, which was chartered in April 1816.

His defense of the South American Revolution against Spanish rule broke ground for the Monroe Doctrine. In 1820, when Missouri's proposed statehood threatened the balance between free and slave states, Clay emerged as "the Great Compromiser," holding a unique political position through his status as a Southerner and a slaveholder on the one hand and as a friend to Northern industry on the other.

Under his solution, known as the Missouri Compromise, Missouri entered the Union as a slave state, Maine entered as a free state to preserve the balance, and slavery was prohibited thereafter in any other new state north of 36°30'.

Land issue

The Panic of 1819 and the ensuing economic depression helped shape the public lands policy proposed in Clay's American System. To achieve stability in the West, Clay favored land prices low enough for men of average means yet sufficiently high to protect the region from undesirable emigrants and to maintain the supply of workers needed by manufacturers.

In opposing the transfer of public lands to control by the states, Clay advocated congressional distribution of public land proceeds to the states for use toward education, internal improvements, and colonization. Despite the failure of his land bills in 1832 and 1833, Clay articulated what became the Whig party's position on public land issues.

From the very first, Clay wanted to include the newly independent Spanish-American states in his system. As early as 1818, Clay indicated that the system of political democracy and commercial freedom should operate throughout the hemisphere, while tariffs could protect the Americas from further entanglements with Europe.

Although the declaration of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823 fulfilled the political aspects of the system, Southerners in Congress were able to obstruct Clay's continued attempts to establish its commercial policies.

Nor was he any more successful as Secretary of State from 1825 to 1829. Yet Clay is still considered by many to have been the first North American Pan-Americanist.

A leader of the Jeffersonian Republican party, he was defeated for president in 1824. He was Secretary of State under John Quincy Adams.

Andrew Jackson accused Clay and Adams of a "corrupt bargain" to elect Adams instead of Jackson in 1824. Clay and Jackson became bitter enemies.

Andrew Jackson would go on to easily defeat Adams in the election of 1828 and then defeat Clay four years later in the election of 1832.

Forming the Whig Party

Clay formed the Whig Party in 1832 to support what he called "The American System," involving a National Bank, promotion of industrialization through tariffs, and support for internal improvements like canals and railroads.

Clay sought the presidency in the 1840 election but was passed over at the Whig National Convention by William Henry Harrison. When Harrison died and his vice president ascended to office, Clay clashed with Harrison's successor, John Tyler, who broke with Clay and other congressional Whigs after taking office upon Harrison's death in 1841.

A rich slave owner, he nevertheless brokered a series of North-South compromises over slavery, especially the Compromise of 1850, as well the Missouri Compromise of 1820, the "Corrupt Bargain" Compromise of 1825, the Tariff Compromise of 1833, the Slavery Compromises of 1837-39, the Texas Annexation Compromise of 1844, and his unwillingness to compromise on a protective banking system scheme in 1841.

He was the foremost advocate of modernization and was greatly admired by aspiring young men like Abraham Lincoln.

Election of 1844

Clay resigned from the Senate in 1842 and won the 1844 Whig presidential nomination.

In 1844, the issue was the annexation of Texas, which Clay opposed, and his Democratic opponent James K. Polk supported. Polk won, and Texas was annexed.

Whig's opposition was consistent with their beliefs in controlled expansion in a market economy. Clay opposed the immediate annexation of Texas, arguing that the gradual development of occupied land was preferential to a policy that could lead to war with Mexico.

Whigs dismissed the Democrats' notion that expansion and democracy were intertwined and instead argued that personal and economic prosperity came from ordered progress, harmony, enterprise, and economic growth through the federal government.

The Whigs perceived Texas annexation as a retreat from the foreign policy tenets established in the Federalist period, an attack on union stability, and an invitation to selfishness and fragmentation. Furthermore, Whigs concluded that Democrats carefully concocted annexation in order to pander to the laboring classes and extend slavery.

The ability of the Democrats to make Texas annexation the paramount issue in the election of 1844 and equate territorial expansion with individual freedom was critical to James Polk's defeat of Clay.

Clay strongly criticized the subsequent Mexican–American War (his son Henry Clay Jr. died at the Battle of Buena Vista) and sought the Whig presidential nomination in 1848 but was defeated by General Zachary Taylor, who went on to win the election of 1848.

Compromise of 1850

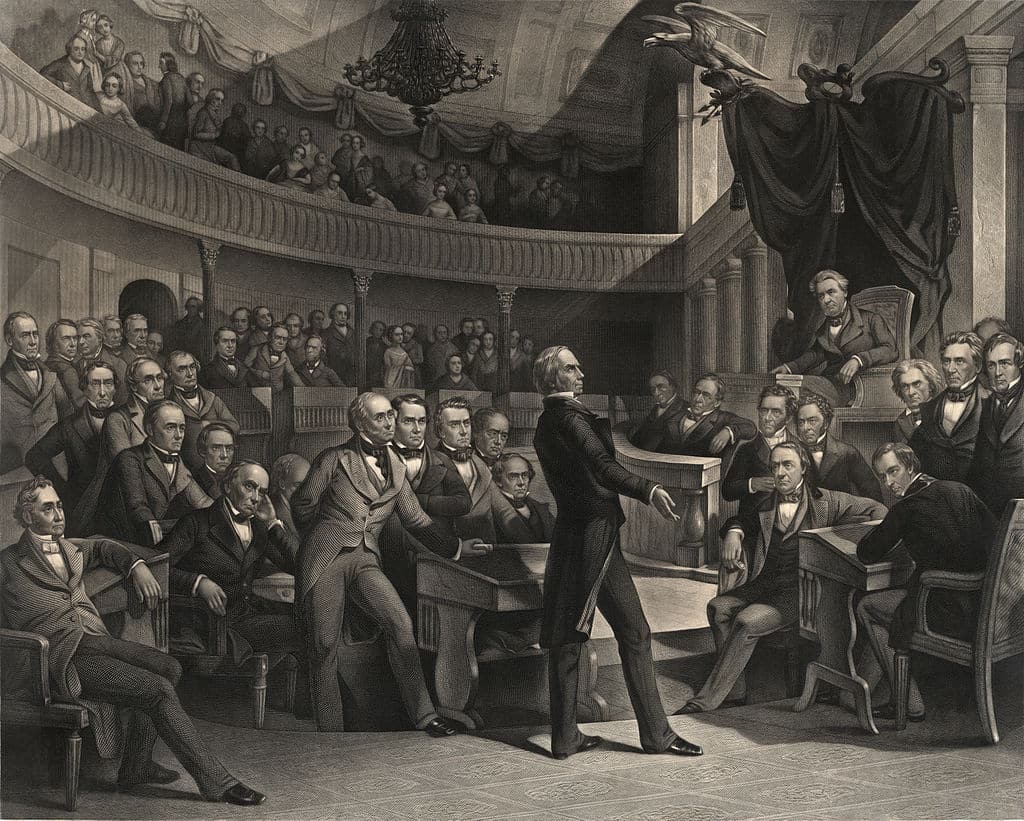

In 1849, Clay returned to the Senate in the last effort to modify the influence of the increasing numbers of extremists, Northern and Southern. His Compromise of 1850 was intended to satisfy both sections, brought California into the Union as a free state, end the slave trade in Washington, DC, and include other provisions intended to balance Southern and Northern interests.

Its most controversial provision, the Fugitive Slave Law, would have guaranteed slaveholders the return of their runaways and thus presumably have done away with the root of sectional differences.

Clay hoped that this, his last and greatest compromise, would forever prevent a civil war. Alongside Clay in the Senate were the other two of the great triumvirate, which had dominated American politics for more than thirty years.

The dying John C. Calhoun demanded the South what was, in effect, equality with the federal government. Daniel Webster, on the other hand, joined with Clay in his famous Seventh of March address and pleaded for an end to sectional strife.

Clay was unable to get his compromise passed, but Democrat Stephen A. Douglas repackaged the compromise so that each component was passed by a different coalition. The compromise effectively postponed war for another decade, but Clay did not live to see the collapse of his Whig party after it lost the 1852 elections.