The Democratic-Republican Party was one of the two political parties in the United States during the First Party System, 1792-1820s.

The Democratic-Republican Party was founded in 1791-92 by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Foreign policy was a central issue, as the party opposed Britain in foreign affairs, opposed the Jay Treaty of 1795, favored France and the French Revolution, and strongly opposed Britain and its friends. In domestic issues, the party opposed Alexander Hamilton's financial program, especially the Bank of the United States.

Jump to:

It opposed the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 and rallied to the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, which emphasized states' rights. The party opposed a strong judiciary and opposed the army and navy. Its guiding principles comprise Jeffersonian Democracy.

The Federalist Party controlled the national government until 1800, then lost and slowly faded away. The Democratic-Republicans elected presidents Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe. By 1900, Republicans dominated Congress and most state governments outside of New England.

Jefferson and Madison created the party in order to oppose the economic and foreign policies of the Federalists, a party created a year or so earlier by Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton.

Foreign policy issues were central; the party opposed the Jay Treaty of 1794 with Britain and supported good relations with France before 1801. The party insisted on a strict construction of the Constitution and denounced many of Hamilton's proposals as unconstitutional.

The party promoted states' rights and the primacy of the yeoman farmer over bankers, industrialists, merchants, and other financial interests.

From 1792 to 1816, the party opposed such Federalist policies as high tariffs, a navy, military spending, a national debt, and a national bank. After the military defeats of the War of 1812, however, the party split on these issues.

Many younger party leaders, notably Henry Clay, John Quincy Adams, and John C. Calhoun, became nationalists and wanted to build a strong national defense.

Meanwhile, the "Old Republican" faction led by John Randolph of Roanoke, William H. Crawford, and Nathaniel Macon continued to oppose these policies.

By 1828, the Old Democratic-Republicans were supporting Andrew Jackson against Clay and Adams.

Founding

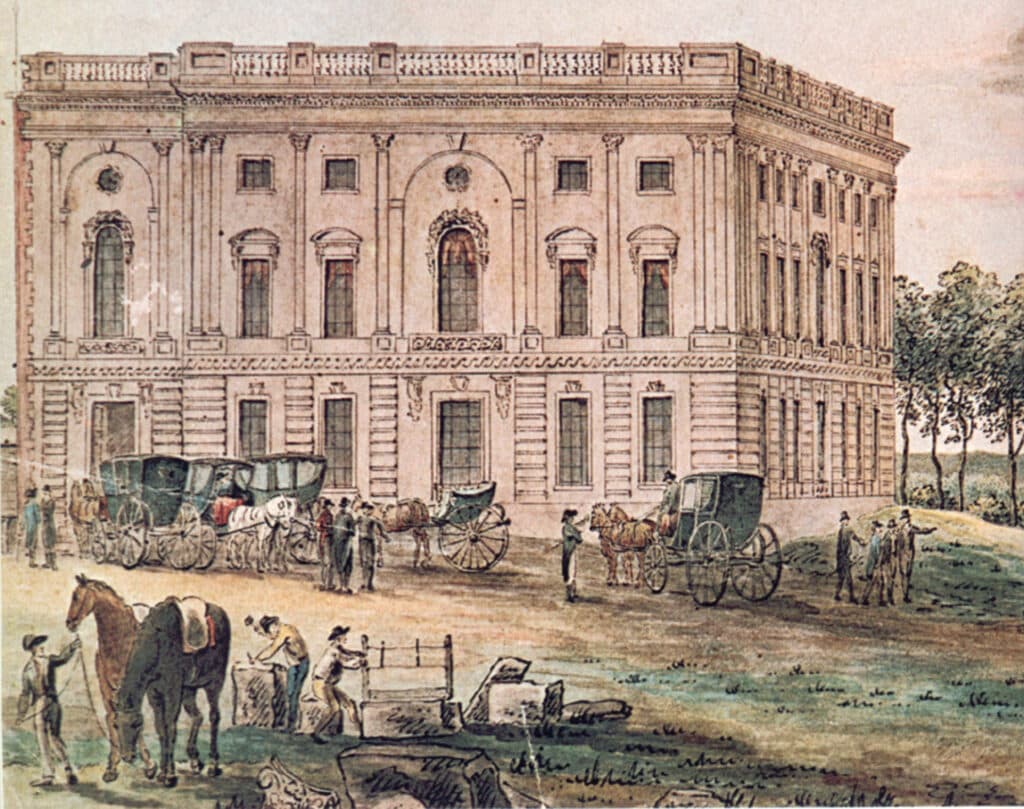

Madison started the party among Congressmen in Philadelphia (the national capital) as the republican party; then he, Jefferson, and others reached out to include state and local leaders around the country, especially in New York and the South.

The new party set up newspapers that made withering critiques of Hamiltonianism extolled the yeomen farmer, argued for strict construction of the Constitution, supported France over Britain as those two nations warred for control of Europe, and opposed any efforts to strengthen the national government as the Federalist Party was proposing.

Members identified themselves as Republicans, Jeffersonians, or Jeffersonian Republicans; their Federalist opponents often called them Democrats or combinations of these.

Presidential Elections of 1792 and 1796

The elections of 1792 were the first ones to be contested on anything resembling a partisan basis. In most states, the congressional elections were recognized, as Jefferson strategist John Beckley put it, as a "struggle between the Treasury department and the republican interest."

In New York, the candidates for governor were John Jay, a Federalist, and incumbent George Clinton, who was allied with Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans.

In 1796, the party made its first bid for the presidency with Jefferson as its presidential candidate and Aaron Burr as its vice presidential candidate. Jefferson came in second in the electoral college and became vice president.

He was a consistent and strong opponent of the policies of the John Adams administration. Jefferson and Madison, through the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, announced the “Principles of 1798,” which became the hallmark of the party.

The most important of these principles were states' rights, opposition to a strong national government, skepticism in regard to the federal courts, and opposition to the Navy and the Banks of the United States.

Jeffersonians saw themselves as champions of republicanism and viewed the Federalists as pro-British supporters of the aristocracy, not of the people.

The party itself originally coalesced around Jefferson, who diligently maintained an extensive correspondence with like-minded republican leaders throughout the country.

George Washington frequently warned against the growing sense of "party" emerging from the internal battles between Jefferson, Madison, Hamilton, Adams, and others in his administration.

As tensions in Europe increased, the two factions increasingly found themselves on different sides of foreign policy issues, with the Republicans favoring neutral ties with both France and England.

The Democratic-Republicans opposed Hamilton's national bank and his belief that a national debt was good for the country. They strongly distrusted the elitism of Hamilton's circle, denouncing it as "aristocratic," and they called for state's rights.

Above all, they disagreed with Hamilton's sense of the Constitution as an elastic, growing document. They feared this interpretation would allow the national government to centralize power.

The fierce debate over the Jay Treaty in 1794–95 transformed those opposed to Hamilton's policies from a loose movement into a true political party. To fight the treaty, the Jeffersonians "established coordination in activity between leaders at the capital, and leaders, actives and popular followings in the states, counties, and towns.

Organizational strategy

The new party invented some of the campaign and organizational techniques that were later adopted by the Federalists and became standard American practice. It was especially effective in building a network of newspapers in major cities to broadcast its statements and editorialize in its favor.

Fisher Ames, a leading Federalist, used the term "Jacobin" to link members of Jefferson's party to the terrorists of the French Revolution.

He blamed the newspapers for electing Jefferson; they were, he wrote, "an overmatch for any Government.... The Jacobins owe their triumph to the unceasing use of this engine; not so much to skill in the use of it as by repetition."

Just as important was effective party organization of the sort that John J. Beckley pioneered. In 1796, he managed the Jefferson campaign in Pennsylvania, blanketing the state with agents who passed out 30,000 hand-written tickets, naming all 15 electors.

Thus, he told one agent, "In a few days, a select republican friend from the City will call upon you with a parcel of tickets to be distributed in your County.

Any assistance and advice you can furnish him with as to suitable districts & characters, will I am sure to be rendered." Beckley was the first American professional campaign manager, and his techniques were quickly adopted in other states.

The emergence of the new organizational strategies can be seen in the politics of Connecticut around 1806, which has been well-documented by Cunningham. The Federalists dominated Connecticut, so the Democratic-Republicans had to work harder to win.

In 1806, the state leadership sent town leaders instructions for the forthcoming elections. Every town manager was told by state leaders "to appoint a district manager in each district or section of his town, obtaining from each an assurance that he will faithfully do his duty."

Then the town manager was instructed to compile lists and total up the number of taxpayers, the number of eligible voters, how many were "decided republicans," "decided federalists," or "doubtful," and finally to count the number of supporters who were not currently eligible to vote but who might qualify (by age or taxes) at the next election.

These highly detailed returns were to be sent to the county manager. They, in turn, were to compile county-wide statistics and send it on to the state manager. Using the newly compiled lists of potential voters, the managers were told to get all the eligible people to the town meetings and help the young men qualify to vote.

At the annual official town meeting, the managers were told to "notice what republicans are present, and see that each stays and votes till the whole business is ended. And each District Manager shall report to the Town-Manager the names of all republicans absent, and the cause of absence if known to him." Of utmost importance, the managers had to nominate candidates for local elections and to print and distribute the party ticket.

The state manager was responsible for supplying party newspapers to each town for distribution by town and district managers. This highly coordinated "get-out-the-vote" drive would be familiar to modern political campaigners but was the first of its kind in world history.

Election of 1800

The party's electors secured a majority in the election of 1800, but by oversight, an equal number of electors cast votes for Jefferson and Burr.

The tie sent the election to the House, and Federalists there blocked any choice. Finally, Hamilton, believing that Burr would be a poor choice for president, arranged for Jefferson to win. Starting with 1800 in what Jefferson called the “Revolution of 1800,” the party took control of the presidency and both houses of Congress, beginning a quarter century of control of those institutions.

A faction called “Old Republicans” opposed the nationalism that grew popular after 1815; they were stunned when party leaders started a Second Bank of the United States in 1816.

In 1804, the party's Congressional caucus for the first time created a sort of national committee, with members from 13 states charged with "promoting the success of the republican nominations."

That committee was later disbanded and did not become permanent. Unlike the Federalists, the party never held a national convention but always relied on its Congressional caucus to select the national ticket.

That caucus, however, did not deal with legislative issues, which were handled by the elected Speaker and informal floor leaders. The state legislatures often instructed members of Congress on how to vote on specific issues.

More exactly, they "instructed" the Senators and "requested" the Representatives. On rare occasions, a Senator resigned rather than follow instructions.

The opposition Federalist Party, suffering from a lack of leadership after the collapse of Hamilton and the retirement of John Adams, quickly declined; it revived briefly in opposition to the War of 1812, but the extremism of its Hartford Convention of 1815 utterly destroyed it as a political force.

By 1820, the Federalists were no longer acting as a national party; there was little to hold the Democratic-Republican Party together. William H. Crawford, in 1824, was the last nominee by the Congressional nominating caucus, but the majority of the party boycotted the caucus.

Crawford finished third in the election that year, behind John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. The Democratic-Republican party split into various factions during the 1824 election, some of which formed the Democratic Party.

Monroe and Adams, 1816-1828

In rapidly expanding western states, the Federalists had few supporters. Every state had a distinct political geography that shaped party membership.

In Pennsylvania, the Democratic-Republicans were weakest around Philadelphia and strongest in Scotch-Irish settlements in the west. Members came from all social classes but came predominantly from the poor, subsistence farmers, mechanics, and tradesmen.

After the War of 1812, partisanship subsided across the young republic. People called it the Era of Good Feeling.

James Monroe narrowly won the party's nomination for President in Congress over William Crawford in 1816 and defeated Federalist Rufus King in the general election.

In the early years of the party, the key central organization grew out of caucuses of Congressional leaders in Washington.

However, the key battles to choose electors occurred in the states, not in the caucus. In many cases, legislatures still chose electors; in others, the election of electors was heavily influenced by local parties that were heavily controlled by relatively small groups of officials.

Without a significant Federalist opposition, the need for party unity was greatly diminished, and the party's organization faded away.

James Monroe ran under the party's nominal banner in 1820 but rarely mentioned the party and sought bipartisan consensus.

Monroe faced no serious rival and was nearly unanimously elected by the electoral college. The party's historic domination by the Virginian delegation faded as New York and Pennsylvania became more important. In 1824, most of the party in Congress boycotted the caucus; only a small rump group backed William Crawford.

The Crawford faction included most "Old Republicans," who remained committed to states' rights and the Principles of 1798 and distrustful of the nationalizing program promoted by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun.

Following the lead of former Crawford supporter Martin Van Buren, the Old Republicans mostly supported Andrew Jackson by the late 1820s.

Thomas Jefferson wrote on the state of party politics in the early 1820s:

An opinion prevails that there is no longer any distinction, that the Republicans & Federalists are completely amalgamated, but it is not so. The amalgamation is of name only, not of principle. All indeed call themselves by the name of Republicans because that of Federalists was extinguished in the battle of New Orleans. But the truth is that finding that monarchy is a desperate wish in this country; they rally to the point which they think next best, a consolidated government. Their aim is now, therefore, to break down the rights reserved by the constitution to the states as a bulwark against that consolidation, the fear of which produced the whole of the opposition to the constitution at its birth. Hence, new Republicans in Congress preached the doctrines of the old Federalists and the new nicknames of Ultras and Radicals. But I trust they will fail under the new, as the old name, and that the friends of the real constitution and union will prevail against consolidation, as they have done against monarchism. I scarcely know myself which is most to be deprecated, a consolidation or dissolution of the states. The horrors of both are beyond the reach of human foresight.

In the aftermath of the disputed 1824 election, the separate factions took on many characteristics of parties in their own right.

Adams' supporters, in league with Clay, favored modernization, banks, industrial development, and federal spending for roads and other internal improvements, which the Old Republicans and the Jackson men usually opposed.

Writing in his personal journal in 1826, President Adams noted the difficulty he faced in attempting to be nonpartisan in appointing men to office:

And it is upon the occasion of appointments to the office that all the wormwood and the gall of the old party hatred ooze out. Not a vacancy to any office occurs, but there is a distinguished federalist who started and pushed home as a candidate to fill it, always well qualified, sometimes in an eminent degree, and yet so obnoxious to the Republican party that he cannot be appointed without exciting a vehement clamor against him and the Administration. It becomes thus impossible to fill any appointment without offending one half of the community: the Federalists if their associate is overlooked; the Republicans if he is preferred

Presidential electors were now all chosen by direct election, except in South Carolina, where the state legislatures chose them. White manhood suffrage was the norm throughout the West and in most of the East as well.

The voters, thus, were much more powerful, and winning their votes required complex party organization.

The Jacksonians, under the leadership of Martin Van Buren, built strong state and local organizations throughout the country.

John Quincy Adams was defeated by Andrew Jackson in the election of 1828.

Party name

The name of the party evolved over the period of its rise and decline as a cohesive party. Party members in the 1790s called themselves Republicans or Republicans and voted for what they called the Republican party, republican ticket, or the republican interest; occasionally, other names were used.

Both "Federalist" and "Republican" were positive words in the 1790s, and both parties sometimes claimed them; so Republicans occasionally called themselves Federalist or Federalist Republicans.

The term "Republican" emphasizes devotion to republicanism. The word "republican" was used by most Americans in the late 18th century to indicate the new nation's political values, especially its devotion to opposition to corruption, elitism, and monarchies; Jefferson used the term "republican party," meaning those in Congress who were his allies, and supported the existing republican Constitution, in a letter to Washington as early as May 1792. From 1794 through 1823, Jefferson and Madison routinely used the term "Republican" and the "Republican party."

In pre-existing usage, "party," where it did not have the overt negative sense of "faction," often meant a loose coalition or collective political influence; the Democratic-Republicans included some personal or single-issue state organizations, like the Clintonians of New York or the "correspondents" of Pennsylvania.

They continued to be sometimes referred to by personal names; not merely Jefferson, but also James Madison, William Branch Giles, and Charles Pinckney.

Their Federalist opponents often called them "Democrats" or "Jacobins" as an insult, referring to mob rule or to The Terror stage of the French Revolution; although "democrat" and "republican" had been used almost equivalently in 1792-3 (and, for the political philosophy, earlier.)

A Democratic society cited a dictionary to argue they were the same in 1794. In 1798, former President George Washington wrote, "You could as soon scrub the blackamore white, as to change the principles of the profest Democrat; and that he will leave nothing unattempted to overturn the Government of this Country."

Equally, the Republicans called Federalists "aristocrats," "monarchists," and "monarcrats," decrying Hamilton's openly professed adoration of Britain and the British governing structure.

After 1802, some local organizations slowly began merging "Democratic" into their own name and became known as the "Democratic Republicans." A few members of the Party were even referring to themselves as Democrats by 1812.

Gammon claimed that "Party nomenclature began to take distinctive shape, locally at least, during the campaign of 1824. At the beginning of that contest, the one party name in existence was 'Republican.'"

The term "National Republican" was first applied to the Adams-Clay faction in New York during the latter stages of the campaign of 1824. In New York state politics, the name "Democratic" was revived in 1824.

In 1818, there had been a split in the New York Democratic-Republican Party, with DeWitt Clinton leading one faction and Martin Van Buren the other. The latter faction was dubbed by its enemies the "Bucktails," and about the same time, began to refer to itself as the "Democratic" party.

The term "Republican," however, was still used to indicate both "Bucktails" and Clintonians.

James Wilson used "democractical" in juxtaposition to "monarchial" or "despotic" in one speech to describe the new Constitution to the Pennsylvania Convention in 1787. According to American lexicographer Noah Webster, the choice of the name was:

…a powerful instrument in the process of making proselytes to the party. The influence of names on the mass of mankind was never more distinctly exhibited than in the increase of the democratic party in the United States. The popularity of the denomination of the republican party was more than a match for the popularity of Washington's character and services and contributed to the overthrow of his administration.

A related grassroots movement, the Democratic-Republican Societies, arose in 1793–94; the use of "democratic" was supported by the French minister, Citizen Genet, a Girondin. It was not formally affiliated with the new party; though some local Jeffersonian republican leaders were also leaders of the societies.

There were some three dozen of these societies; they did not nominate tickets or attempt to control legislatures, as the Republicans did. The Federalists soon denounced the Democratic-Republican Societies.

Both "Federalist" and "Republican" were positive words in the 1790s, and both parties sometimes claimed them; so Republicans occasionally called themselves Federalist or Federalist Republicans. The party also came to call itself "Democratic Republicans" as well as "Republicans" during Madison's term of office; some members called themselves "Democrats."

Claims to the party's heritage

The Democratic Party is often called "the party of Jefferson," while the modern Republican Party is often called "the party of Lincoln," although the modern party system with a liberal, economically populist Democratic Party and a conservative, free-market-oriented Republican Party did not arise until the 1930s when many progressive elements of the Republican Party switch support to the ideals of the New Deal affecting a switch in orientation that has continued to the modern day.

The Democratic-Republican party split into various factions during the 1824 election, based more on personality than on ideology.

When the election was thrown to the House of Representatives, House Speaker Henry Clay backed Secretary of State John Quincy Adams to deny the presidency to Senator Andrew Jackson, a longtime personal rival and a hero of the War of 1812.

Jackson's political views were unknown at the time. At first, the various factions continued to view themselves as Republicans. Jackson's supporters were called "Jackson Men," while Adam's supporters were called "Adams Men."

The Jacksonians held their first national convention as the "Republican Party" in 1832. By the mid-1830s, they referred to themselves as the "Democratic Party," although they also continued to use the name "Democratic-Republicans," and the name was not officially changed until 1844.

Many politicians of the Democratic Party have emphasized their party's lineage to Jefferson and the Democratic-Republican Party. Martin Van Buren wrote in his Inquiry Into the Origin and Course of Political Parties in the United States that the party's name had changed from Republican to Democratic and that Jefferson was the founder of the party.

Thomas Jefferson Randolph, the eldest grandson of Jefferson, gave a speech at the 1872 Democratic National Convention and said that he had spent eighty years of his life in the Democratic-Republican Party.

The Adams/Clay alliance became the basis of the National Republican Party, a rival to the Jacksonian party. This party favored a higher tariff to protect U.S. manufacturers, as well as public works, especially roads. Former members of the defunct Federalist Party joined the party.

After Clay's defeat by Jackson in the 1832 presidential election, the National Republicans were absorbed into the Whig Party, a diverse group of Jackson opponents. Taking a leaf from the Jacksonians, the Whigs tended to nominate non-ideological war heroes such as William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor as their presidential candidates.

The modern Republican Party was founded in 1854 as an anti-slavery party. Most northern Whigs soon defected to the new party.

The name was chosen to harken back to Jeffersonian ideals of liberty and equality, but not those of limited government or states' rights, ideals that Abraham Lincoln and many members of the new party sought to revive together with Clay's program of using an active government to modernize the economy.

In 1991, the United States Senate passed by voice vote "A bill to establish a commission to commemorate the bicentennial of the establishment of the Democratic Party of the United States." It was introduced by Democratic Senator Terry Sanford and cosponsored by 56 Senators.

The Jeffersonian Party claims to be the modern party closest in ideology to the Democratic-Republican Party and bases its platform on the writings of Jefferson.

Several other parties, including the United States Libertarian Party and the Constitution Party, lay claim to his heritage.